For a brief overview, check out our blogs

Tenant Protections

Market-Rate Housing Production

Learn more with our policy briefs

Summary

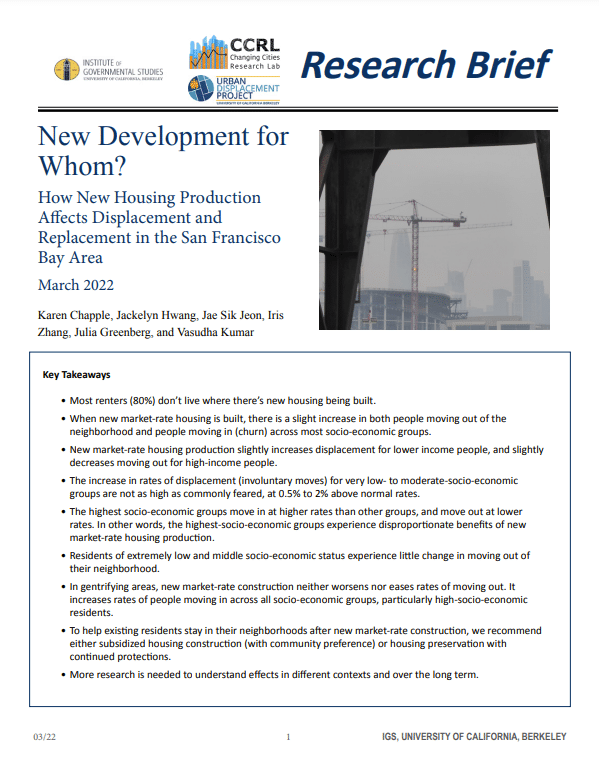

Market-Rate Housing Production

Tenant Protections

Subsidized Housing Production

Where do people move to?

Summary

All people deserve a safe place to call home. Safe and stable housing is foundational to the rest of our lives—without it, it’s hard to meet our needs around health, school, jobs, or community. Good housing brings us security and dignity.

However, California has a housing affordability crisis and a shortfall in housing production that will reach 1.5 million units by 2025. Displacement—involuntary moves—disrupts lives and livelihoods, often forcing residents to move far from their jobs, schools, and social networks. The effects can be long lasting.

Lawmakers need to target spending to the most effective programs, but it’s hard to know what’s effective without robust, current data. The most-cited rent stabilization studies are from the ‘80s and ‘90s, and the most recent studies of market-rate production focus on housing prices, not displacement. Researchers have struggled to pinpoint the impacts of solutions like new housing production and tenant protections on residents, due to the lack of fine-grained data. Because of this unavailability of appropriate data, there is little research available to inform which housing solutions will be most effective in stabilizing communities so that those who wish to stay are able to, even as newcomers arrive.

Download the full report here

In the context of the San Francisco Bay Area’s tight housing market, this study—completed in collaboration with the Changing Cities Research Lab at Stanford University—overcomes previous data challenges for the first time by building unique (and cross-validated) datasets on mobility and linking them to a bespoke block-level housing construction and tenant protections database. You can download the housing construction and tenant protections data for your own research by clicking on the button below; see the README for an explanation of the variables. Our mobility data is not available for public use.

This is the most granular data on displacement in the Bay Area (or anywhere) ever produced. With this never-before-seen data, we are able to pinpoint how market-rate development, subsidized development, and tenant protections (both just cause eviction and rent stabilization) impact both direct and indirect displacement, by looking at movement both out of and into local neighborhoods over a four-year period.

Our findings improve on those of other studies because we are able to examine the socio-economic status of households that move, rather than assuming that households have the same characteristics as their overall neighborhood. By accounting separately for both moves in and moves out by Socio-Economic Status, this study is better able to pinpoint neighborhood change.

Our findings reveal that equitable solutions will require more than just new housing production and tenant protections. While a focus on multi-family development helps, it won’t solve the problem. To address the housing affordability crisis and mitigate displacement and exclusion, policymakers must pursue not only preservation of unsubsidized affordable housing, but also bolder initiatives such as social housing–the provision of rental or homeownership units affordable at a moderate income or below, run by a public or nonprofit entity. Matching the urgency of the housing crisis would require wide implementation and investment.

As a specific strategy, preserving multi-unit rental properties that are at risk of becoming unaffordable can help increase access for low-socio-economic status communities. San Francisco’s Small Sites Acquisition and Rehab Program is a good example of this approach. Other potential approaches include tenant opportunity to purchase programs, property tax incentives for building owners, condominium conversion restrictions, and community land trusts.

Key Findings

- For all socio-economic groups and across the nine-county Bay Area, new market-rate construction in a neighborhood results in more people moving in.

- When new market-rate housing is built in a neighborhood, there’s a slight increase in people of all income levels both moving in and moving out—churn. The increase in rates of displacement (involuntary moves) for very low- to moderate-socio-economic groups are not as high as commonly feared, at 0.5% to 2% above normal rates.

- Because displacement disrupts lives and livelihoods, even one displaced family is one too many. Policymakers have a moral obligation to prevent displacement. Fortunately, there are tools that work; our leaders should use them much more—at a level that matches the urgency of the housing crisis.

- Our research revealed three core findings:

- More market-rate production primarily serves the most affluent.

- Rent stabilization helps residents of the lowest socioeconomic status stay in their neighborhoods, but it also prevents other low-income people from moving in.

- Just cause eviction protections help the lowest socioeconomic status residents remain in gentrifying neighborhoods, where displacement pressures may be especially strong for vulnerable residents. In these hot-market areas, just cause can reduce the likelihood of displacement by up to 1% for the lowest income residents.

- Together, these findings reveal that equitable solutions to the housing crisis will require more than just new housing production and tenant protections–these are complementary solutions, but not enough.

- To address the housing affordability crisis and mitigate displacement and exclusion, policy makers must pursue not only the preservation of unsubsidized affordable housing, but also bolder initiatives that substantially expand social housing.

- Social housing is the provision of rental or homeownership units affordable at a moderate income or below, and is run by a public or nonprofit entity. To work, it would need to be widely implemented, requiring government investment at levels that match the urgency of the housing crisis.