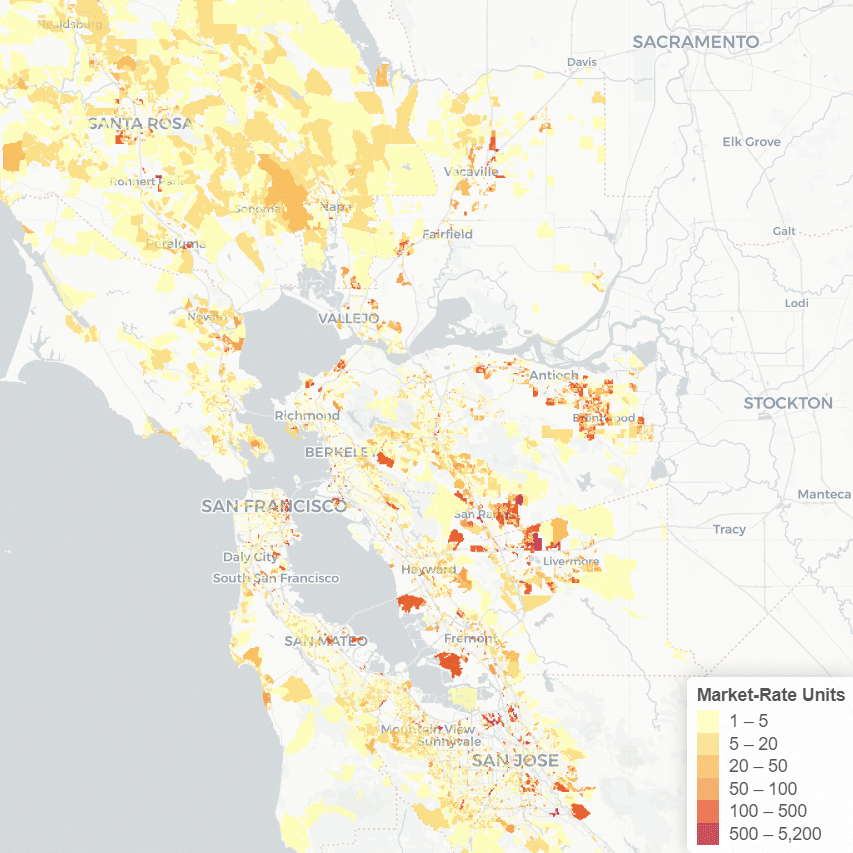

While Silicon Valley often makes headlines for innovative technology and disruptive ideas, local families are experiencing a very different kind of disruption: displacement from their homes. Santa Clara County, home to the immense wealth of Silicon Valley and California’s third largest city San Jose, is no exception to the problems of housing insecurity facing the greater Bay Area. Rents and housing prices have far outpaced relatively stagnant wages for working class jobs, and the county has an estimated shortage of over 58,000 affordable homes for low-income renters. As a result, 3 out of every 4 low-income renters in the county are rent-burdened, meaning they pay more than 30 percent of their income on rent each month. According to our latest maps, 34 percent neighborhoods in the county are at risk of or already experiencing processes of gentrification and/or displacement. Residents are feeling these changes on the ground. Just last week, community organizations pushed back against the City of San Jose for proposing to sell 10 acres of public land to Google; advocates instead suggested that the city steward this land for affordable housing and shelter for residents experiencing homelessness. The City Council did eventually approve the sale, for $110 million.

In this blog post, we summarize some of the key findings from our study on the consequences of displacement. This study is an expansion of our previous study in San Mateo County, and both seek to understand and document the impacts of housing insecurity and displacement for individuals and families. These studies illustrate how being displaced does not simply mean finding a new place to live: it has serious consequences for children, employment, housing, health, and well-being. This study was based on in-depth surveys our team conducted with 124 low- or moderate-income renters in Santa Clara County. The research was a collaborative effort between our team and the diligent staff at our partner organizations: Bay Legal and the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley, who worked with us to design the survey and to recruit potential study respondents.1 For more detailed data from this study, as well as further information on study design, take a look at the full data summary here.

Our findings illustrate the depth of housing insecurity for low-income renters in Santa Clara County. Strikingly, almost half of study respondents thought it was likely they would have to leave their home in the coming year. Our respondents who had already been displaced were often pushed into more precarious housing and greater financial burden. Additionally, survey results revealed a widespread fear of retaliation from landlords – and that such fear is founded. Over half of displaced respondents reported that their landlord took retaliatory actions that contributed to their being displaced. Finally, the survey shows that when people are displaced from their homes, many are displaced from their neighborhoods, when people are displaced from their homes, many are displaced from their neighborhoods, impacting social support networks and capacity for community advocacy.

Housing Instability and a Relationship of Fear between Tenants and Landlords

Over half of respondents said they were not comfortable talking to their landlord about repairs or other housing concerns, and over 1 in 3 feared landlord retaliation for raising concerns or requesting repairs. Retaliation can take many forms, such as evictions, harassment, or rent increases.2 Fear of retaliation may force families to endure poor conditions that compromise their health and safety. Pests and mold, for example, contribute to asthma onset and severity. In fact, 80 percent of respondents reported at least one significant housing issue, such as mold or defective heating systems.

Respondents who had been displaced echoed just how commonplace it is for landlord to retaliate after a tenant request repairs, raises a concern, or otherwise exercises their rights as a tenant. Over half of people who were displaced, 56 percent, said that their landlord took retaliatory actions that contributed to their being displaced. Landlords often retaliated by raising the rent or evicting tenants.

One respondent explained, “There was a lot of negligence. When I brought these things up, I believe strongly that she retaliated against me – and mostly because I [spoke] Spanish . . . I finally had the courage to stand up to her and demand repairs inside of the home . . . It was about me and the other neighbors and my community that live in fear. . . I got evicted.”

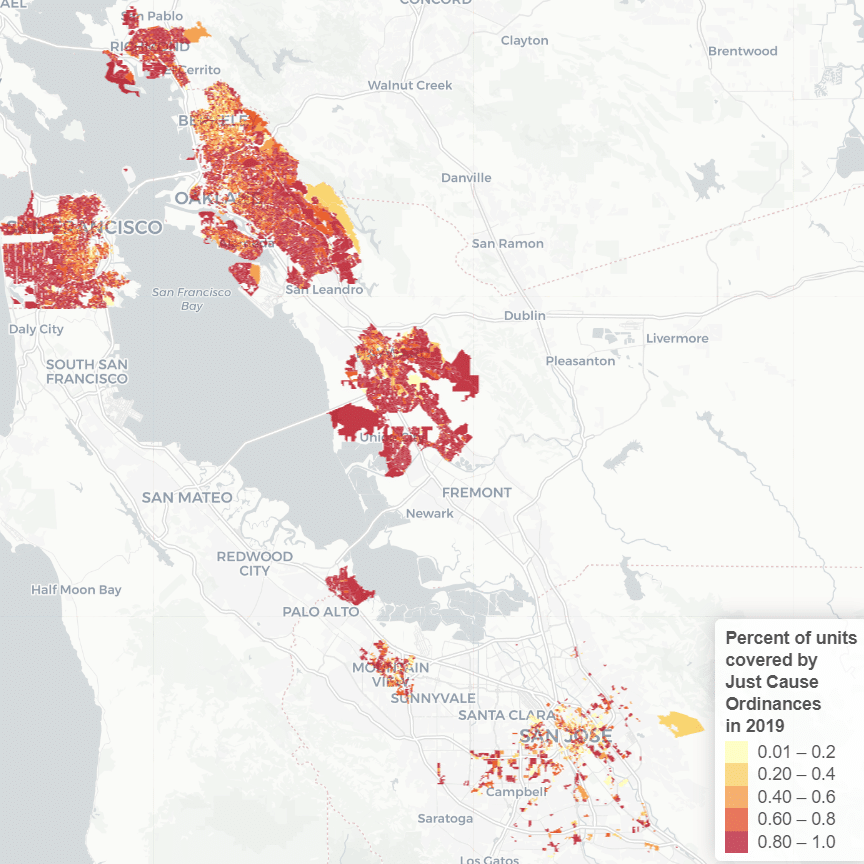

The City of San Jose passed just cause eviction protections in 2017, as this study was in progress, which is designed to mitigate retaliatory evictions. However, these protections only apply to people living in apartment buildings with three or more units, which leaves 37 percent of San Jose’s rental housing without these protections.

Financial hardship, poor quality housing, and the fear of retaliation were common factors motivating one of the most alarming findings from the study: almost half of respondents thought it was likely they would have to leave their home within the next year. Where will these families go? Many will face financial barriers and steep competition on the rental market, which tends to be even more challenging for families with children, people of color, and people with housing assistance vouchers like Section 8.

The Search for Stable, Affordable Housing

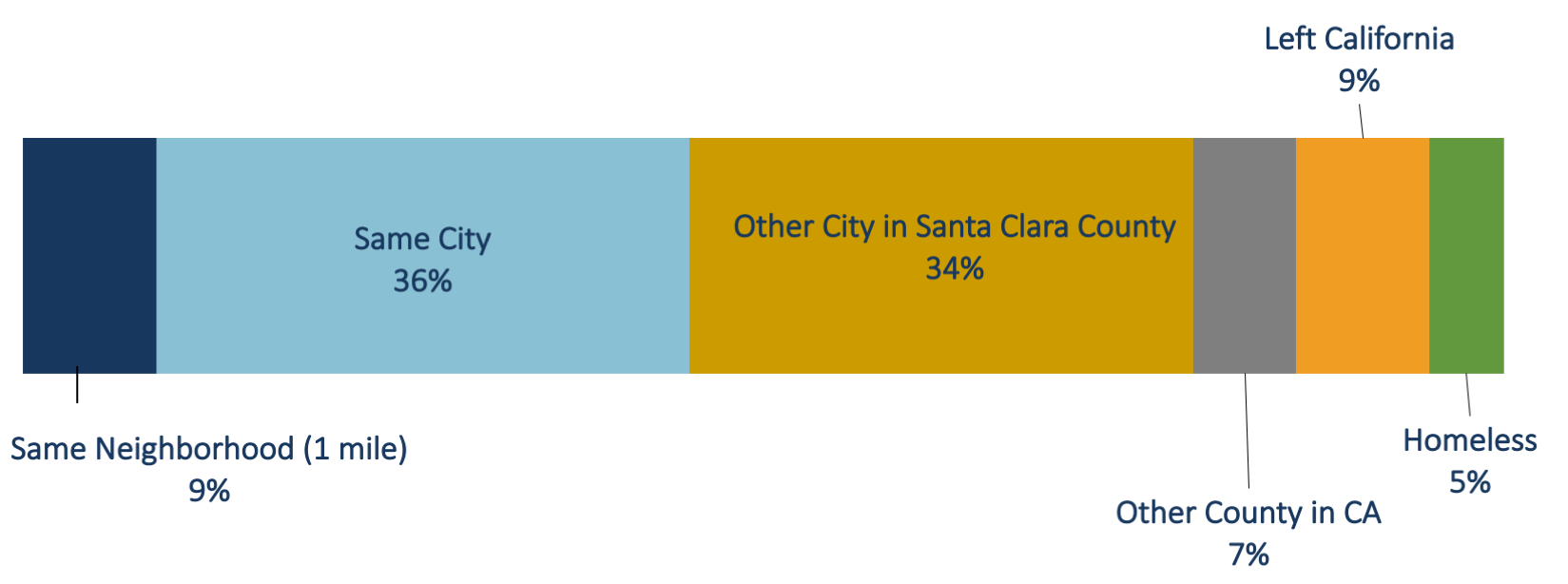

Respondents who had been displaced looked for new housing near and far, and most families faced significant barriers finding a new home. In the end, 45 percent of displaced respondents found a new place to live in their same city. However, far fewer – only 10 percent – found a new home within a mile of their previous home. Another 34 percent moved to a new city within Santa Clara County, and sixteen percent left the county altogether. Over half of those who left the county left the state. While some respondents were able to stay in their city upon being displaced, or even their neighborhood, that was not the case for the majority of respondents.

Consistent with our prior research, we found that respondents who were displaced were more likely to ended up in precarious housing situations, such as living in a hotel, “doubling up” with friends or family, or couch-surfing. Twenty percent of displaced households were precariously housed, compared to only 4 percent of households who had not been displaced.

Despite being more likely to live in precarious housing conditions, households that had been displaced were also more likely to be severely rent burdened, meaning

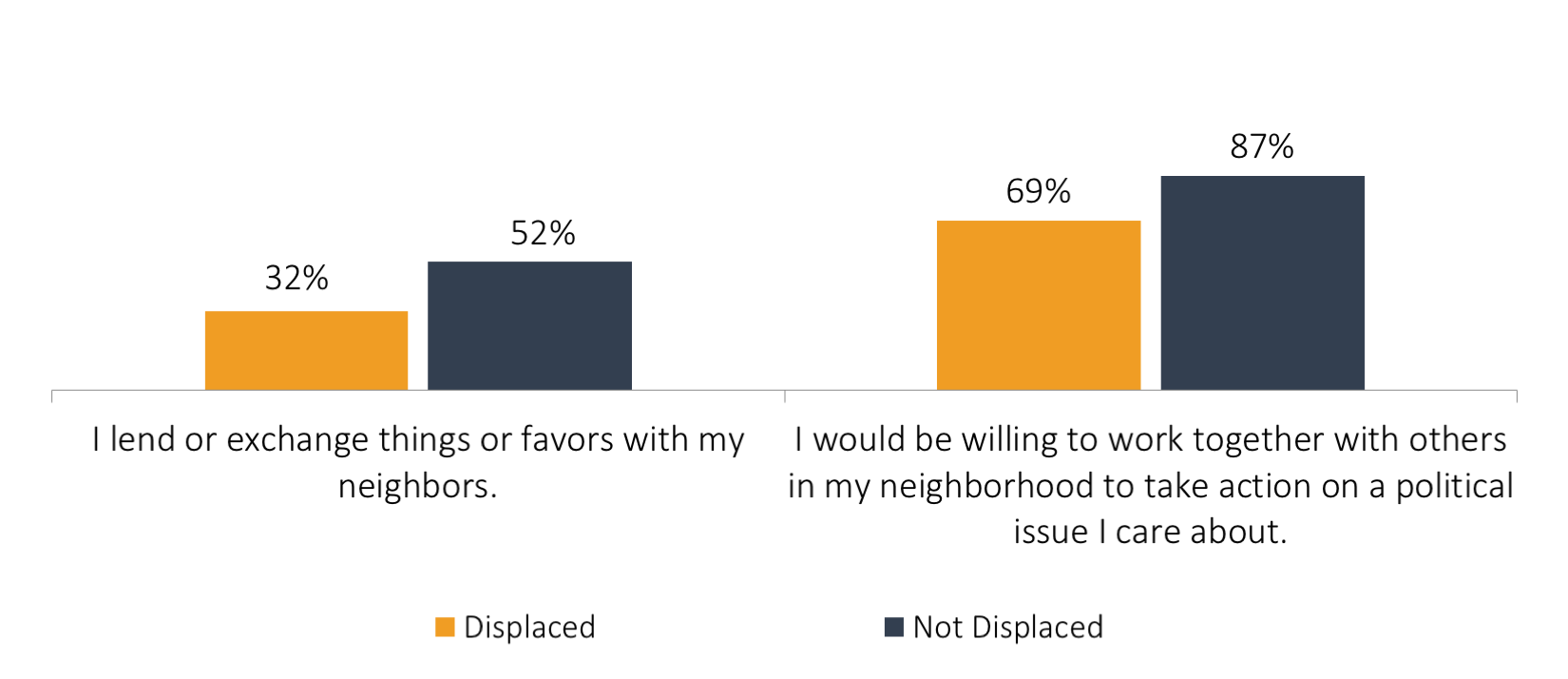

Disrupting Social Support Networks and Community Advocacy

As families are displaced from their homes to new neighborhoods, their social support network and communities may also be disrupted. People who were displaced were less likely to be able to rely on their neighbors to lend or exchange items or favors, such as childcare, 32 percent compared to 52 percent, respectively. In a state where childcare is extremely costly, a loss of this kind of support can make a significant difference for families. People who were displaced were also less likely to be willing to take collective, political action in their community, 69 percent compared to 87 percent, respectively.

While this study is based on a relatively small sample, these findings offer important evidence of the extreme instability and precarity facing low- and moderate-income renters in Santa Clara County. Just like we saw in our San Mateo County study, tenants are struggling to afford their homes, and the hot housing market incentivizes landlords to employ neglect and fear to keep their costs low or push tenants out. These practices have serious implications for household stability and health. There are immediate impacts when a family is forced to leave their home, which are often the most visible parts of displacement. The full consequences of displacement, however, are long-lasting and reverberate through communities.

This study further underscores what we see in the news each day: people are struggling. And it is our neighbors who already carry the weight of financial hardship and exclusion – families with young children, seniors, people of color – who are also forced to endure an unequal share of our current housing system’s failures. While an array of much-needed housing policies – in protections, production and preservation – can and will make a difference over the next several years and decades, protecting tenants can happen today. Cities and counties need to step up to protect their residents from displacement and its enduring consequences.

For more detailed data from this study, as well as further information on study design, take a look at the full data summary here. Both this study and our previous study in San Mateo County were made possible by grants from Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

Notes

1. Survey respondents were sorted into two groups: people who had been displaced from their home in the past two years and people who had not been displaced in the last two years. Displaced refers to any kind action outside of the control of the tenant that causes them to leave their home, including formal evictions as well landlord harassment or unsafe conditions.

2. Although San Jose has a rent stabilization ordinance, 72 percent of rental units in San Jose are were built after 1979 and/or are single-family homes, which are excluded from rent stabilization ordinance per state law.