Check out our policy brief

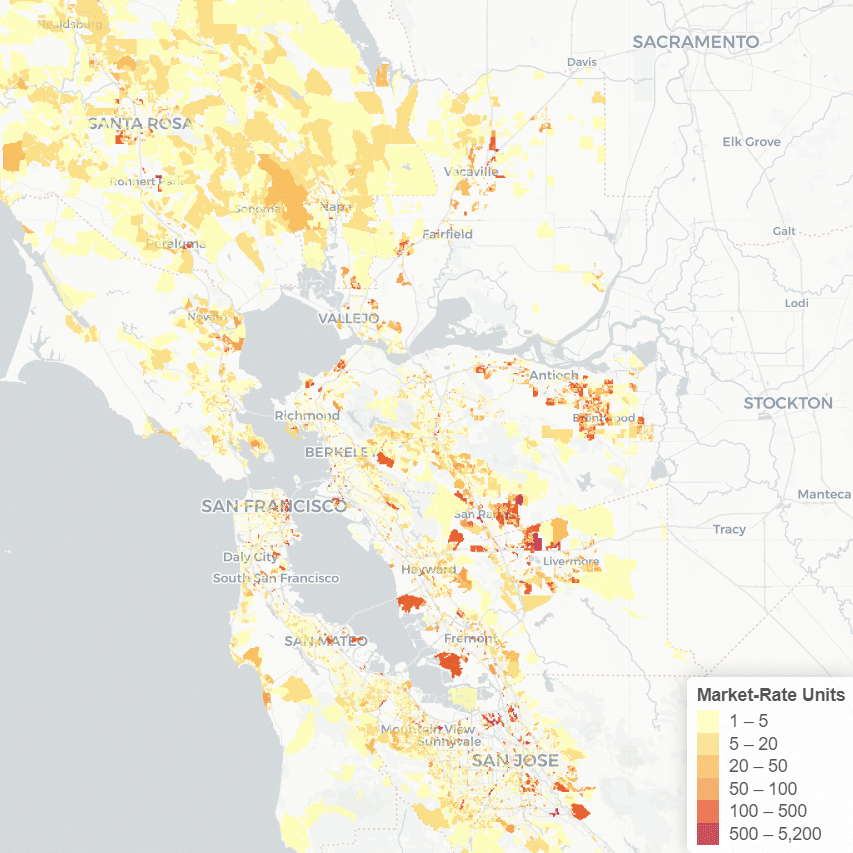

Number of new units built by census block, 2000-2019. Source: UDP New Housing Production Database

All people deserve a safe place to call home. Safe and stable housing is foundational to the rest of our lives—without it, it’s hard to meet our needs around health, school, jobs, or community.

Yet California has a housing affordability crisis, and a shortfall in housing production that will reach 1.5 million units by 2025, according to the most conservative estimates. It is clear that more homes are needed in order to alleviate the market pressures making it difficult for so many to find a place to live. However, when new housing is actually built in a neighborhood, it raises a lot of questions. Will this new housing make space for more people of all incomes to move in? Will it catalyze change in the neighborhood, raising rents and ultimately pushing people out? Who benefits from this new housing, and who loses out?

Past research has struggled to answer these questions, largely due to a lack of fine-grained data. As a result, most studies make assumptions about individuals based on aggregate data. For example, instead of examining household-level moves, studies have often assumed that all individuals in a census tract have the same characteristics as the average person in the tract. This makes it difficult for policymakers to know which housing solutions will be most effective in stabilizing communities so that those who wish to stay are able to, even as newcomers arrive.

In partnership with the Changing Cities Research Lab at Stanford University, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Urban Displacement Project overcomes these data challenges for the first time by building unique (and cross-validated) datasets on mobility and linking them to a bespoke block-level housing construction database. In our newly released policy brief, we analyze how the number of new market-rate units built in a census block group impacts the migration patterns of households of different socio-economic status between 2006 and 2019. We describe our main findings below.

Contrary to common belief, building new housing creates only modest churn.

When new market-rate housing is built, there is a slight increase in both people moving out of the neighborhood and people moving in (churn) across most socio-economic groups. However, the highest socio-economic groups move in at higher rates than other groups, and move out at lower rates. In other words, the highest socio-economic groups experience disproportionate benefits of new market-rate housing production.

It is important to remember that most renters (80%) don’t live where there’s new housing being built.

New market-rate housing production slightly increases displacement for lower income people, and slightly decreases moving out for high-income people.

We found that when new market-rate units are built in a neighborhood, lower socio-economic groups are somewhat more likely to move out while the highest socio-economic groups are actually less likely to move out. Residents of extremely low and middle socio-economic status experience little change in moving out of their neighborhood.

In gentrifying areas (with both fast-rising housing prices/rents and a large influx of high-income or highly-educated residents), new market-rate construction neither worsens nor eases rates of moving out. It increases rates of people moving in across all socio-economic groups, particularly high-socio-economic residents.

Tenants and advocates often worry most about the potential displacement impacts of new buildings in areas experiencing gentrification. The concern is that these new buildings will only be affordable to wealthier newcomers and will catalyze neighborhood change, raising nearby rents and forcing lower-income residents to leave.

However, these buildings seem to help to alleviate pressure on the local housing stock, providing newcomers with places to live and freeing up units for existing residents. Our study found that new market-rate construction in gentrifying areas does not have much of an effect on most households’ likelihood of moving out. However, the new construction does increase in-migration for all socio-economic groups, suggesting that market-rate buildings in gentrifying neighborhoods benefit more than just the wealthy.

Solving the housing affordability crisis requires more ambitious approaches.

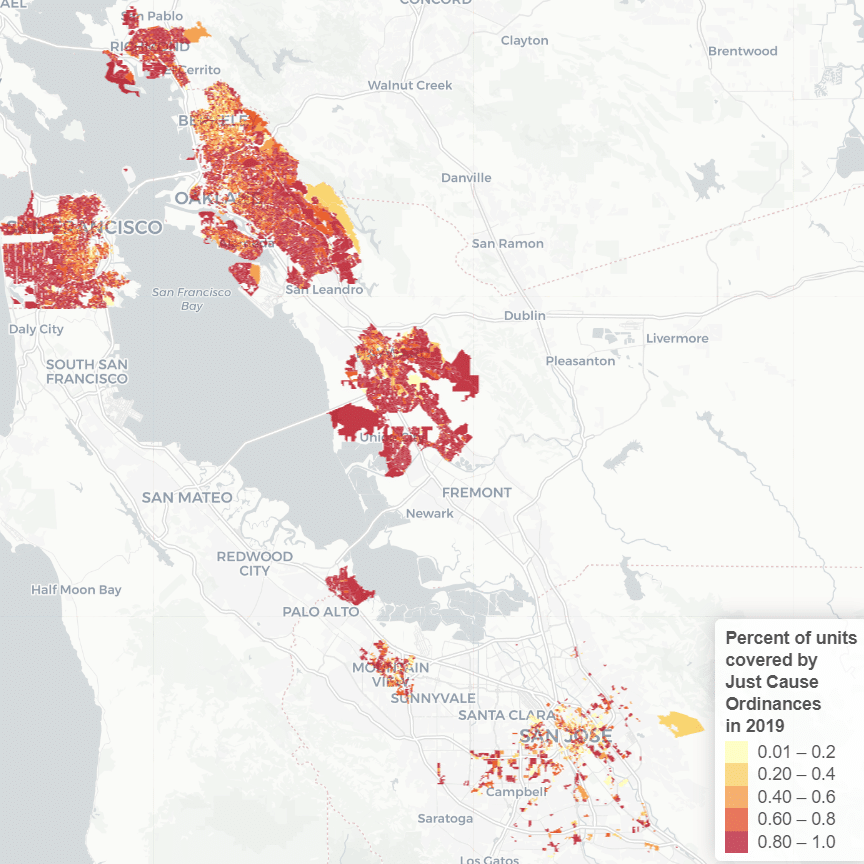

New market-rate housing productions, even when coupled with tenant protections, will not be enough to address the housing affordability crisis and mitigate displacement and exclusion. Policy makers must pursue not only the preservation of unsubsidized affordable housing, but also bolder initiatives that substantially expand social housing. Social housing is the provision of rental or homeownership units affordable at a moderate income or below, run by a public or nonprofit entity. To work, it would require government investment at levels that match the urgency of the housing crisis.

After decades of dealing with a growing crisis, California may finally be ready to take action. AB 2053, the California Social Housing Act, would create a new California Housing Authority to produce and preserve social housing affordable to Californians of different income levels, funded by cross-subsidies. If implemented at scale, AB 2053 is a promising step in the right direction.