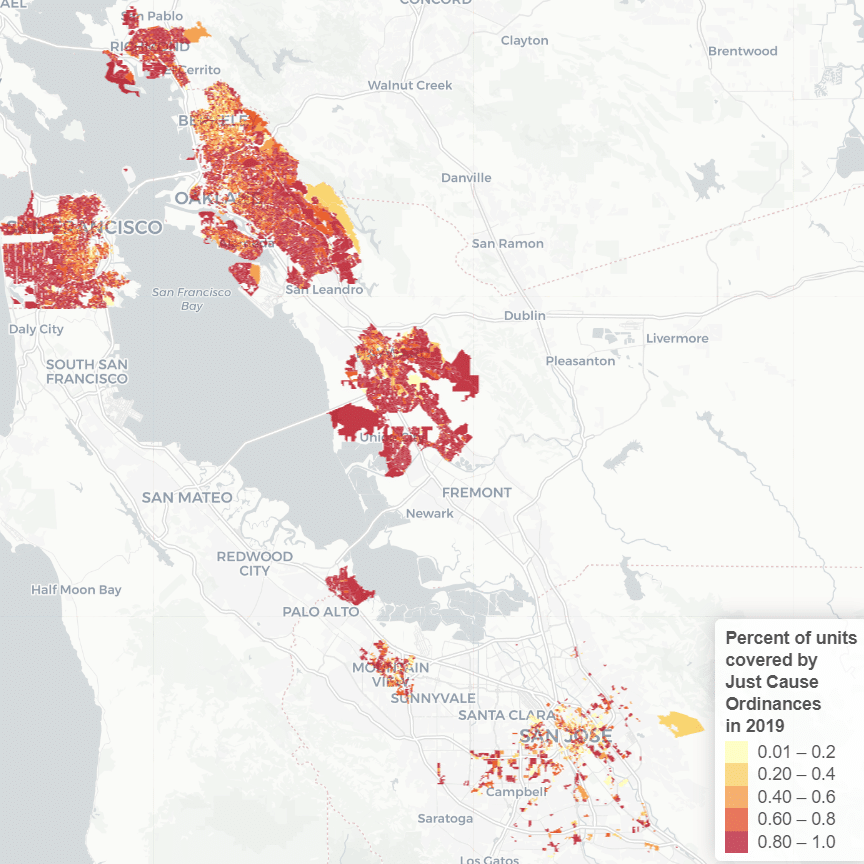

Source: UDP Tenant Protections Database

All people deserve a safe place to call home. Safe and stable housing is foundational to the rest of our lives—without it, it’s hard to meet our needs around health, school, jobs, or community.

Yet California has a housing affordability crisis, and a shortfall in housing production that will reach 1.5 million units by 2025. In the face of a structural housing shortage, local governments across the state have increasingly turned to tenant protection policies to help low-income households avoid displacement. Without tenant protections, residents can be vulnerable to changes in the local housing market that may be outside their control, like substantial hikes in rent costs and arbitrary evictions. However, as housing advocates push for greater protections, do tenant protections actually help address displacement effectively? And do they have unintended consequences?

Lawmakers need to target spending to the most effective programs, but it is hard to know what policies are most effective in stabilizing communities without robust, current data. There is little research specifically evaluating the impacts of tenant protections on displacement. The most-cited rent stabilization studies are from the ‘80s and ‘90s, and the most recent studies of market-rate production focus on housing prices, not displacement.

In part due to lack of data, past research has measured displacement by comparing the number of low-income residents in a neighborhood across two time periods, but it is difficult to determine whether residents actually moved out of the neighborhood or simply changed income level.

In partnership with the Urban Displacement Project at the University of California, Berkeley, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Changing Cities Research Lab overcomes these data challenges by building unique datasets on mobility (i.e., whether a household moves out of or into a neighborhood) and linking them to a bespoke block-level tenant protection database. For the first time, we are able to examine the impacts of specific housing interventions on the mobility of residents on the individual- and household-levels.

In our policy brief on tenant protections, we describe our findings on the impact of rent stabilization and just cause for evictions on the migration patterns of residents in the Bay Area between 2006 and 2019. Below, we highlight our main takeaways.

Relatively few units in the Bay Area are covered by tenant protections. San Francisco houses the greatest share of units with tenant protections, while protections are more sporadic in the South Bay.

Our research focuses on two specific forms of tenant protections: rent stabilization and just cause eviction. Rent stabilization generally refers to a set of policies restricting the amount landlords can raise rent in a given year, along with provisions that exempt new construction and bring rents to market rate once tenants move out. Just cause eviction policies forbid property owners from evicting tenants except under certain specified circumstances, such as nonpayment of rent, thereby protecting tenants from arbitrary evictions.

In the Bay Area, coverage of housing units by just cause ordinances tends to be much more comprehensive than rent stabilization coverage. San Francisco houses the greatest share of units with tenant protections, while protections are more sporadic in the South Bay. Since tenant protection ordinances in most jurisdictions include both just cause for evictions and rent stabilization protections, there is significant overlap between the two; however, in most jurisdictions, more units in each jurisdiction are subject to just cause than rent stabilization.

Both rent stabilization and just cause reduce displacement for residents of the lowest socio-economic status.

Our research finds that rent stabilization decreases the likelihood of moving out of a neighborhood for lowest socio-economic status residents. This indicates that the ordinance is helping the most vulnerable residents stay in place in their communities.

In the Bay Area’s gentrifying areas (i.e., neighborhoods increasing in housing values or rents, while also experiencing an influx of high-income, high-educated residents) both rent stabilization and just cause help reduce displacement for residents of the lowest socio-economic status. Displacement pressures may be especially strong for vulnerable residents in these hot-market areas, and tenant protections are helping to alleviate housing market pressures and reduce displacement for lowest socio-economic status residents.

Tenant protections are limited to protecting existing tenants. They do not help to expand housing opportunities and may have exclusionary impacts.

Tenant protections do help reduce displacement for the most vulnerable residents, but we also find that they may have exclusionary impacts in the Bay Area. Put simply, as the percentage of units covered by rent stabilization increases in Bay Area neighborhoods, fewer lowest-SES people move in. In gentrifying neighborhoods, neither rent stabilization nor just cause encourages these residents to move in and take advantage of tenant protections. These exclusionary impacts may be yet another symptom of limited housing availability in the Bay Area. In the context of few options that are affordable for all income levels, tenant protections alone are inadequate to expand access to stable, affordable housing, particularly for lowest-SES renters.

Solving the housing affordability crisis requires more ambitious approaches.

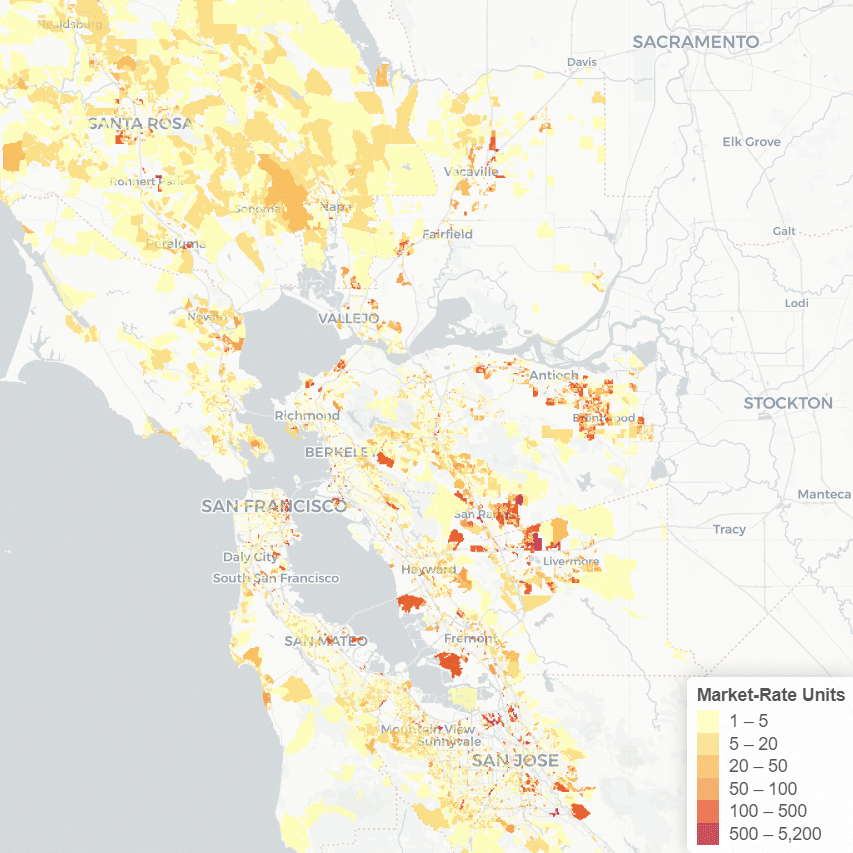

Tenant protections are a critical tool to address displacement and keep residents in their homes. Nevertheless, our full report reveals that while protecting existing tenants and building more market-rate housing are necessary and complementary solutions, they are not enough. To address the housing affordability crisis and mitigate displacement and exclusion, policymakers must pursue not only the preservation of unsubsidized affordable housing, but also bolder initiatives that substantially expand social housing—rental or homeownership units affordable at a moderate income or below, run by a public or nonprofit entity.

Matching the urgency of the housing crisis will require wide implementation and investment. AB 2053, the California Social Housing Act, would create a new California Housing Authority to produce and preserve social housing affordable to Californians of different income levels, funded by cross-subsidies. If implemented at scale, AB 2053 is a promising step in the right direction.