Uber’s recent announcement that they plan to shift their headquarters from San Francisco to Oakland was met with mixed reactions: some cheered the jobs this would bring to downtown Oakland, while others worried about the impact this change would have on ongoing gentrification in a city that has a complicated history surrounding low-income housing.

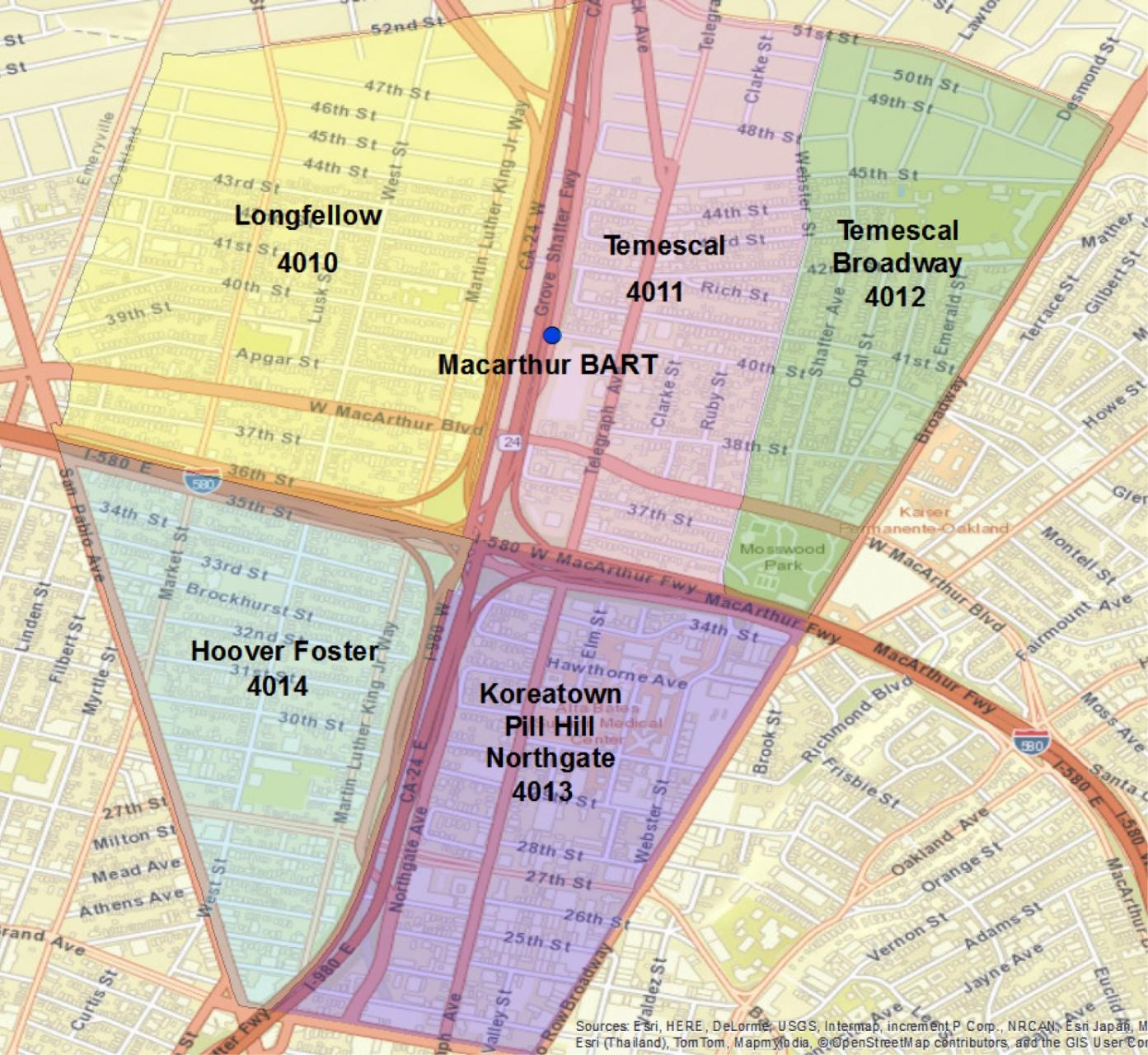

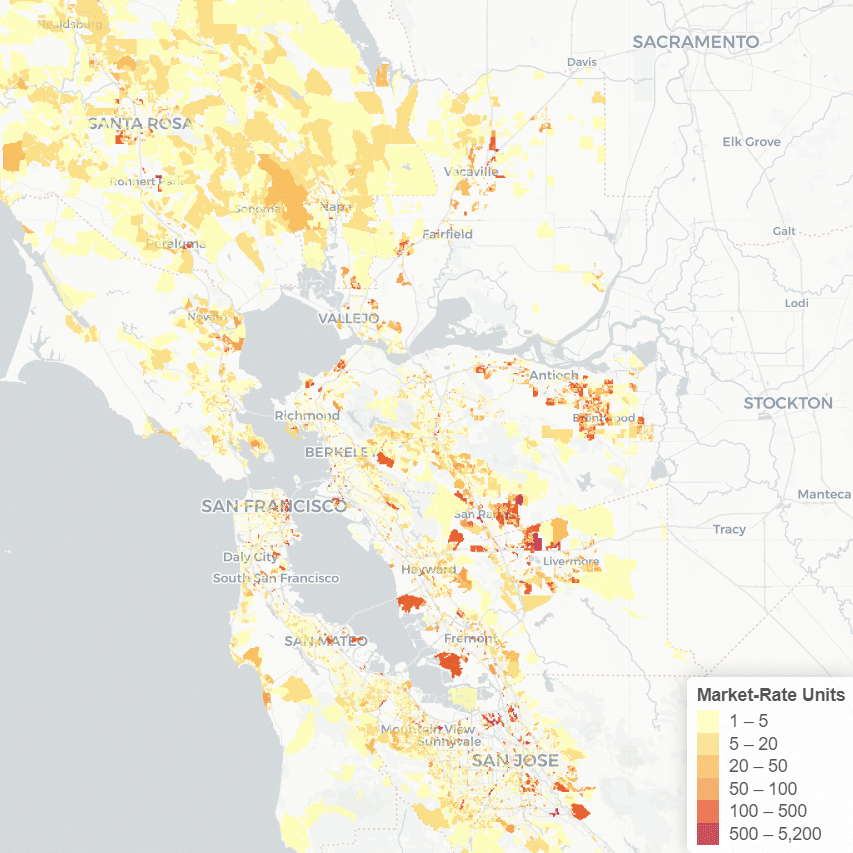

Some of Uber’s employees—current and future—are likely to move to Oakland, and many will likely come to call the neighborhoods surrounding the Macarthur BART station—an easy bike ride or walk to Uber—home. With close proximity to transit, significant (and increasing) retail options, and a historic housing stock (i.e. homes with “good bones”) this neighborhood has seen dramatic change in recent years. From 1980 to 2013, the area highlighted in the map has experienced a 12% increase in population; the proportion of African-Americans has decreased from 65% to 34%; while the white population has increased from 25% to 30% and Latino population has risen from 4% to 19%. Income and level of education have also risen.

These changes are consistent with our other findings that document the patterns of gentrification and displacement in neighborhoods with access to transit. However, a closer look at the Macarthur BART case reveals considerable variation at the neighborhood level. For example, in terms of educational attainment, the proportions of adults who have completed a 4-year degree range from only 16% in the Hoover-Foster neighborhood, to 56% in Temescal-Broadway. While Temescal has seen rising property values, lower crime, and significant commercial investment, the other neighborhoods are struggling with higher poverty, unemployment, and crime rates. Of 195 foreclosures in the area between 2006-2014, 67% were west of the Grove-Shafter Freeway. And though significant commercial changes have come to the Telegraph Avenue corridor in Temescal, resulting in new restaurants and stores that yielded a 32% increase in sales tax revenue since 2005, other areas have seen little in the way of new business development.

New retail shops in Temescal.

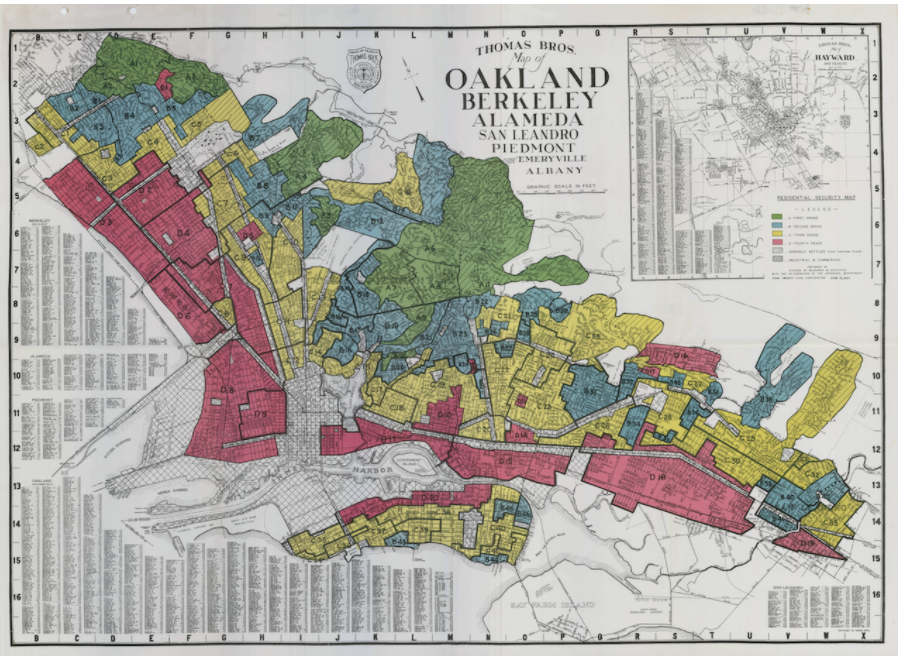

What can explain this variation? While in part related to physical characteristics like the presence of an older housing stock in Temescal, these patterns can be traced back through a history of institutionalized racial discrimination. As Oakland’s African-American population grew during World War II, discriminatory practices like redlining made it near-impossible for them to buy homes east of Telegraph Avenue. The neighborhoods surrounding the present-day BART station became divided, with white ethnic groups (primarily Irish, Italian, and Portuguese) to the east, and African-Americans to the west.

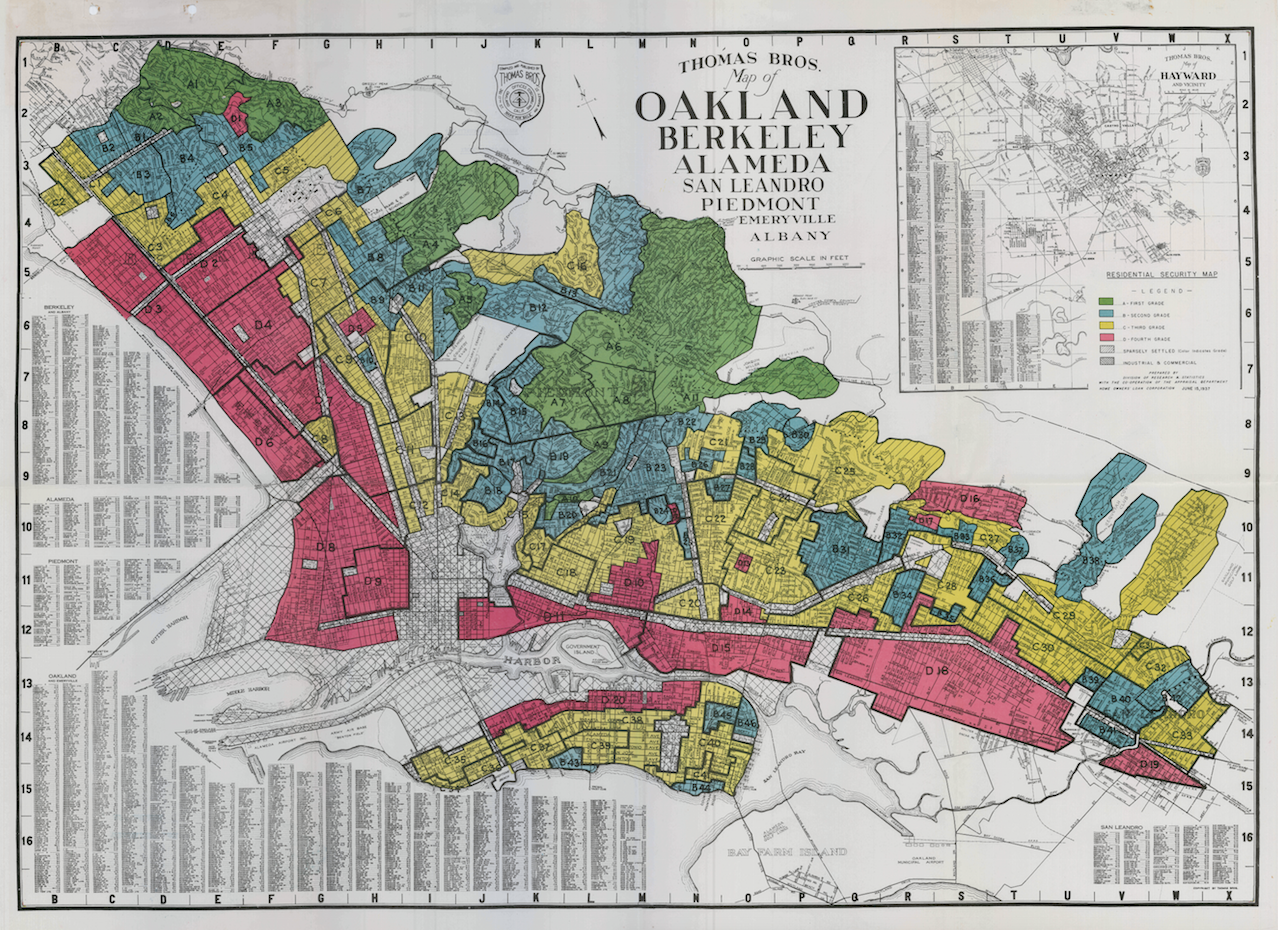

A 1937 map from the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation showing the divide in North Oakland between “Fourth Grade” land to the west and higher-grade land to the east. These regions were used to exclude African-Americans from securing mortgages for homes in higher-grade areas.

When the Grove-Shafter Freeway was constructed in the 1960s, it tore right through the African-American community in this area, ruining long-established local businesses and upsetting these racial divides. This change (along with simultaneous white flight to the suburbs) left the formerly-exclusionary neighborhoods to the east open to African-Americans. However, they inhabited the neighborhood in a new era marked not by industrial job growth, but decline. Coupled with the loss of sales tax revenues from middle class whites leaving the city, the area became depressed; in the 1990s, poverty rates rose. Korean, Ethiopian, and Eritrean residents, responding to low property values, moved in and opened businesses in the neighborhoods to the east of the freeway.

Now, as the economy is improving again and there is investment interest among the middle class and affluent in the area, African-Americans are being pushed out once again–past is prologue.

As the MacArthur BART station area neighborhoods show, even in a place experiencing gentrification overall, change can be spatially specific, with a declining neighborhood sometimes blocks away from a gentrifying one. In a city like Oakland, with tremendous demographic diversity and varying risk of gentrification among its many neighborhoods, neighborhood-specific policy interventions could help make precise, targeted changes to halt displacement.

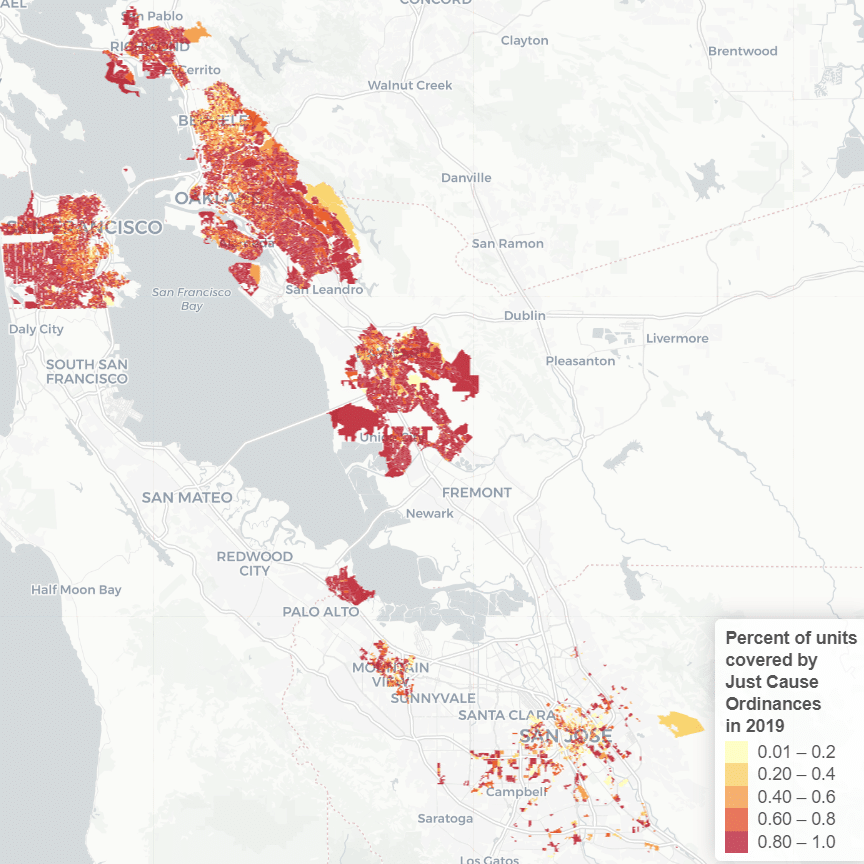

The City of Oakland’s history of handling its low-income housing is less than ideal: it stood by while banks redlined it, under Mayor Jerry Brown, it pursued market-rate development, and it has never passed inclusionary housing or fortified its rent control, lagging Berkeley and San Francisco. Can Uber’s arrival be the catalyst for the city to redefine itself as a robust market that can afford to use regulation to preserve and produce low-income housing?

Perhaps: The city, responding to pressure from community organizations, has started to look into charging an impact fee on market rate housing development to help fund affordable housing. And the new Oakland Housing Cabinet is looking at various market-rate and affordable housing policy solutions that can help lower-income renters and owners, stabilize neighborhoods, and prevent displacement. Uber’s move to downtown Oakland is the latest sign of the city’s growth. The decisions city officials make now in response to these changes will shape its future.