Mapping Displacement and Gentrification in Metro Manila

Metro Manila is an urban region in the Philippines located on the island of Luzon, with a population of over 12.8 million resting on 239 square miles making it the densest region in the country. In the recent decade, Manila has quickly become a city of foreign investment, land speculation, and commercial business centers that strives to be part of the Global South’s catalog of “world-class cities.” Yet with these forms of globalization and development emerge a paradox between the middle and elite classes of the Philippines and the urban poor. As Manila experiences rapid change brought about by economic potential, there is an increasing influx of domestic migrants coming to the capital region in search of employment. The number of people in Manila who cannot afford housing and therefore resort to informal settlements has increased, with the latest estimate approximating 37% of Metro Manila’s residents live in slum areas.

Key Findings

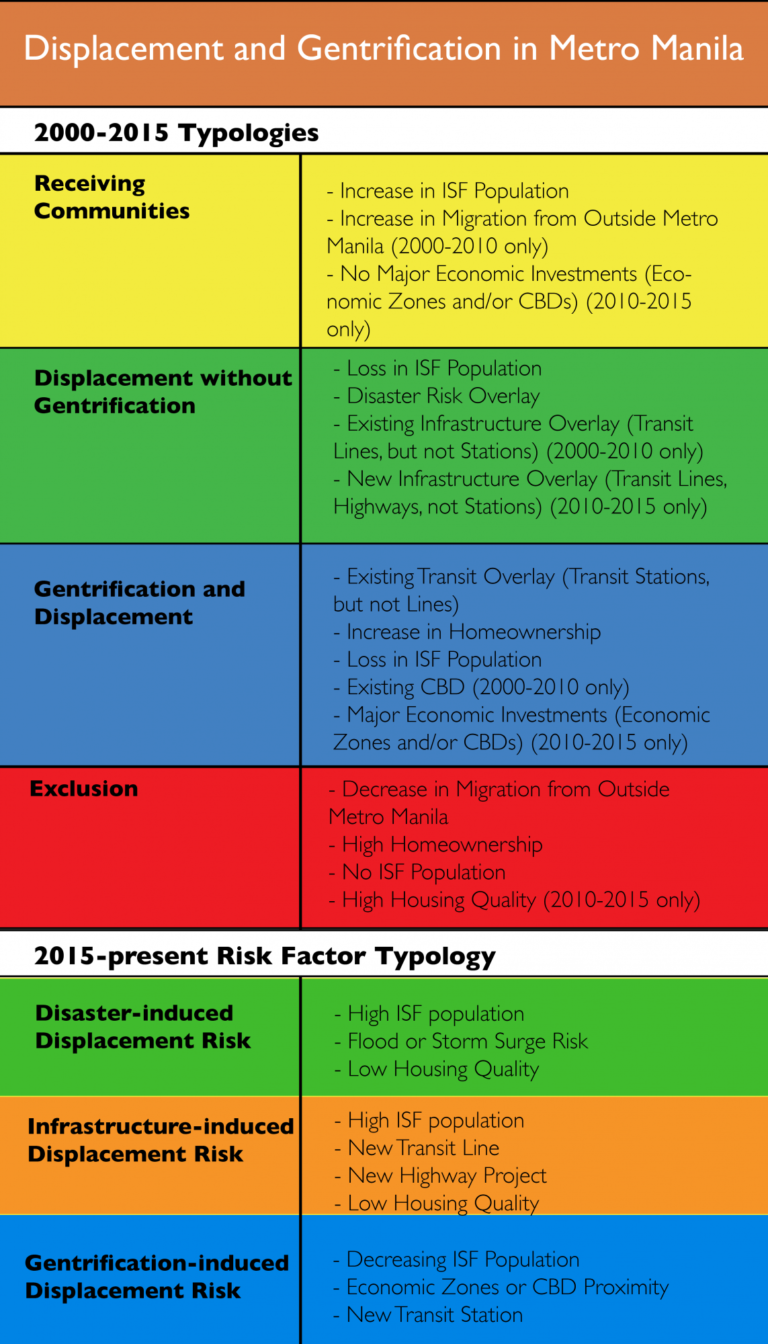

Gentrification and displacement in Metro Manila push Western definitions and epistemologies of these issues and processes. These case studies illustrate that displacement is very much tied to notions of formality and homeownership—middle-class norms that are not inclusive of all members of urban poor communities. Displacement can take different forms: disaster induced, gentrification induced and infrastructure induced. It is realized through government actions of eviction, demolition and dispossession.

Our findings are categorized into four themes:

1. A Changing Metro Manila: The Nation’s Reflection of its Past & Future – urban development is still influenced by the colonial legacies of Spanish and American occupation in the country. The predominance of gated communities and other forms of Western-inspired exclusion through urban design are examples of this. As the country moves into the future, the aspirations of transforming Manila into a “global city” are driven and facilitated by the influx of foreign capital, particularly from the US, mainland China, and returning Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). These range from mega infrastructure projects and master-planned communities geared towards foreign buyers, expats, OFWs, and wealthy Filipinos.

2. Housing Policy and Planning: Striving for Preservation and Equitable Development – Displacement is deeply embedded within Philippine housing policy, which is characterized as an institutionalized process through formalized evictions and relocation. Relocation is often framed as an inevitable process due to infrastructure development and disaster risk reduction and management. Forced displacement constantly sparks the debate between on-site, in-city, and off-site relocation. A majority of subsidized housing created by national government agencies are located in peri-urban areas. The private sector is taking advantage of the gaps in long-term, coordinated government planning and playing an increasing role in urban development – such as the emergence of “unsolicited” infrastructure projects (such as highways and subway lines) initiated by private developers.

3. Conflicting Viewpoints on Development and Informality – The concept of “development” is contested in Metro Manila. For some developing exclusive spaces is seen as a sign of progress – including the sustained pipeline of private spaces and gated communities in the Metro. The conditions of urban informal settler families (ISFs) is a polarizing and political topic. On one hand, ISFs are seen as an obstacle to development, yet are leveraged because of their strong voter turnout and political positioning in urban public officials. For some local government units (LGUs), programs such as the Community Mortgage Program (CMP) and Balanced Housing Rule (akin to Inclusionary Housing policies in the U.S.), are promising, but thus far limited in scale, solutions to housing inequities in Metro Manila.

4. Community Organizing and Resistance – Community Organizing has been a way to empower informal settlers since the 1960’s and has been crucial in instilling the “right to stay” against forced resettlement. Successful efforts such as the People’s Plan, which preserved land and created new social housing for communities along the flood-prone Manggahan Floodway, are examples of community-organized process that is slowly being institutionalized by various levels of government. There is a need to document this history of displacement, community organizing and resistance.