Around the globe, many cities are experiencing a housing affordability crisis. There are few places this crisis is more pronounced than San Francisco and Los Angeles. California’s strict land use regulations hinder us from producing enough housing, particularly infill development, or new buildings on vacant or underutilized land in the urban core.

Yet, with 200,000 units in the pipeline, the San Francisco Bay Area’s housing construction is near its historic pace. The question is, how can the region produce more affordable housing?

The crisis will only get worse as we plan for a more sustainable region. With two million new residents expected in the Bay Area by 2040, the region is proposing to channel 80% of its future growth into 5% of regional land area. To help, cities will get transportation funding and relief from environmental regulation. But that may not be enough to counteract the challenge of finding appropriate sites or even just paying for high-rise residential buildings outside of the region’s major downtowns (San Francisco and San Jose). Rising land prices in the core will also mean higher housing costs. At the same time, the vast majority of new jobs expected in the Bay Area are expected to be low-wage, exacerbating the need for affordable housing.

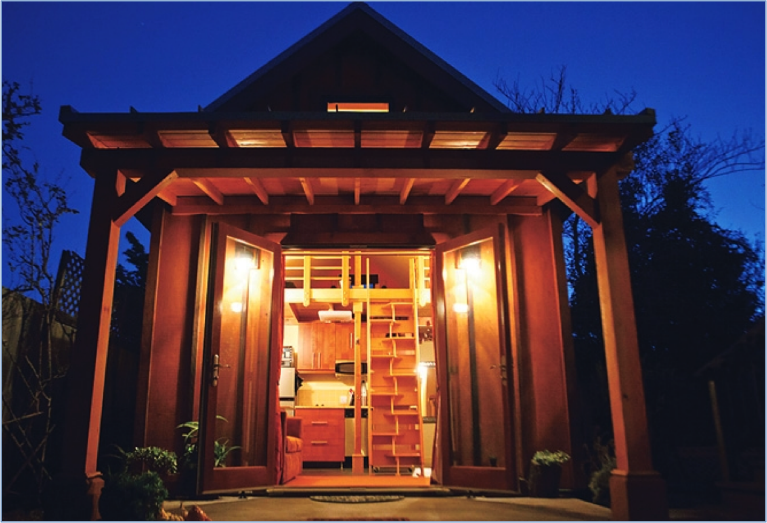

What if the solution is actually in our own backyards? My study with University of Texas-Austin Professor Jake Wegmann, published recently in the Journal of Urbanism, shows that based on the availability of underutilized or vacant land, about half of our infill development in built-up areas like San Francisco’s East Bay should occur in the form of accessory dwelling units, or self-contained, smaller living units, attached or detached from the main home. With relatively low costs (as low as $100,000) and short build time (less than six months), backyard cottages can increase density more efficiently than multifamily projects. They rent for much less, often providing affordable units within affluent neighborhoods and diversifying the housing stock. We calculate that a backyard cottage strategy could yield as many as six times as many affordable units as conventional infill.

What if the solution is actually in our own backyards? My study with University of Texas-Austin Professor Jake Wegmann, published recently in the Journal of Urbanism, shows that based on the availability of underutilized or vacant land, about half of our infill development in built-up areas like San Francisco’s East Bay should occur in the form of accessory dwelling units, or self-contained, smaller living units, attached or detached from the main home. With relatively low costs (as low as $100,000) and short build time (less than six months), backyard cottages can increase density more efficiently than multifamily projects. They rent for much less, often providing affordable units within affluent neighborhoods and diversifying the housing stock. We calculate that a backyard cottage strategy could yield as many as six times as many affordable units as conventional infill.

The question then becomes, what is hindering homeowners from building more cottages? Even in Berkeley, a city that welcomes accessory units, the number of permit applications for home additions still dwarves that for cottages. We argue that the market is blocked largely because of restrictive zoning regulations, particularly parking requirements. One solution has appeared in the form of intermediaries that help homeowners navigate city regulations and manage construction. But the market for these intermediaries is mostly a niche of wealthy elderly homeowners seeking to age in place alongside younger generations.

The question then becomes, what is hindering homeowners from building more cottages? Even in Berkeley, a city that welcomes accessory units, the number of permit applications for home additions still dwarves that for cottages. We argue that the market is blocked largely because of restrictive zoning regulations, particularly parking requirements. One solution has appeared in the form of intermediaries that help homeowners navigate city regulations and manage construction. But the market for these intermediaries is mostly a niche of wealthy elderly homeowners seeking to age in place alongside younger generations.

To address the affordable housing crisis while making our regions more sustainable, a mass market for small-scale infill must emerge. But to create such a market requires a fundamental shift in the conversation. Just as in the debate over climate change, we can argue endlessly on the merits and the means, but in the end, the game-changer will be the costs of inaction – a deepening of the already devastating housing crisis.

Banks currently don’t allow current or prospective homeowners to use income from accessory units to qualify for mortgages. That means that only the homeowners with substantial equity in their homes who can finance the construction of accessory units. Developing a mass market means helping low- and moderate-income homeowners to build – and purchase – homes with accessory units as well. As Wegmann has written, state and national housing finance agencies could adapt their existing programs to provide new mortgage products for new permitted spaces. Eligibility for the loans could be predicated on the home city easing zoning regulations for accessory units.

It took a revolution in mortgage finance to spur the suburbanization of America. It will take a new revolution to make affordable infill possible.

For more information, see “Yes in My Backyard: Mobilizing the Market for Secondary Units,” “Hidden Density in Single-Family Neighborhoods: Backyard Cottages as an Equitable Smart Growth Strategy,” “We Just Built It:” Code Enforcement, Local Politics and the Extralegal Housing Market in Southeast Los Angeles County, Chapter 3 in Planning Sustainable Cities and Regions: Towards More Equitable Development, and five related IURD working papers.