The Parkview Family Apartments in San Jose’s Diridon Station area. Affordable housing like this helped the area to increase its low-income population in recent years, even as major new market-rate housing was constructed, too. Photo source: http://www.eahhousing.org/pages/featureddevelopmentdetail/20

As we have previously shown, the Bay Area’s wave of gentrification is only just beginning . In the face of such dramatic changes—ongoing and future—we conducted an inventory of cities’ anti-displacement policies. Extending that policy lens, we wanted to know: do any places manage to overcome the displacement pressures associated with gentrification and retain their low-income populations?

There were a fair number of places that we expected to gentrify, but did not; these 221 Census Tracts are shown in the below map.

221 Census Tracts (out of 1,580 total) were at risk for gentrification/displacement between 1990 and 2000, but did not experience gentrification between 2000 2013.

Of course, our data only runs through 2013, and neighborhood change can happen fast; some or many of these neighborhoods could be gentrifying now.

Even so, we took a closer look at three of these places: San Francisco’s Chinatown, San Jose’s Diridon Station, and East Palo Alto. Here’s some of what we found.

Anti-Displacement Policies Help

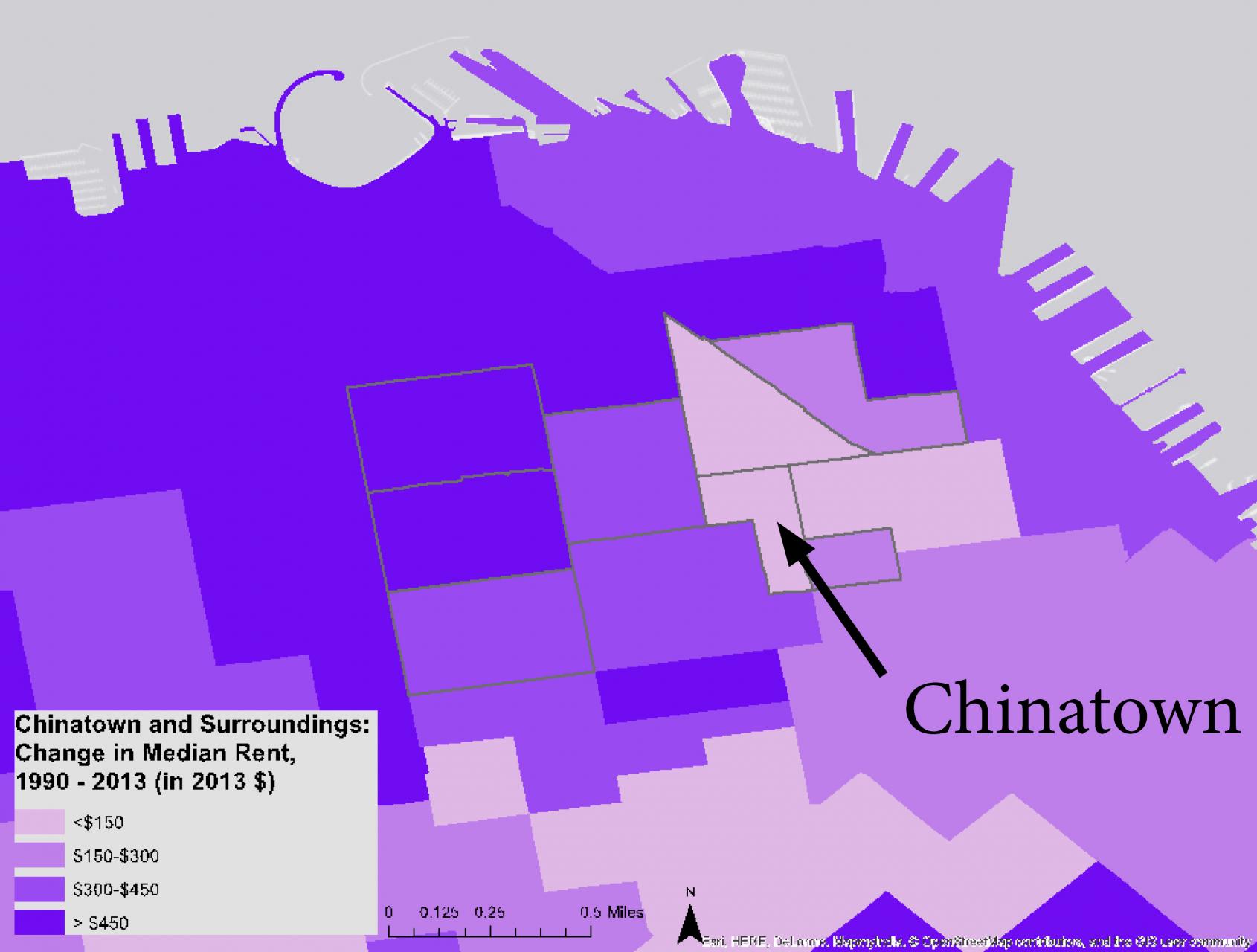

In Chinatown, the community and city undertook a concerted effort in the 1980s to implement policies preserving the low-income population there. The city downzoned the parcels in Chinatown, reducing their development potential, and made demolition extremely difficult.

While the areas surrounding the core of Chinatown have experienced dramatic rent increases, rents in Chinatown itself have grown only slightly. This is likely due to the high proportion of the housing stock in Chinatown that is rent controlled—over 90%–and the effectiveness of the conversion and demolition protections that kept that rent-controlled stock standing.

While rents have risen dramatically in the neighborhood surrounding Chinatown, the core of the neighborhood has stayed affordable, a result of strong anti-displacement protections.

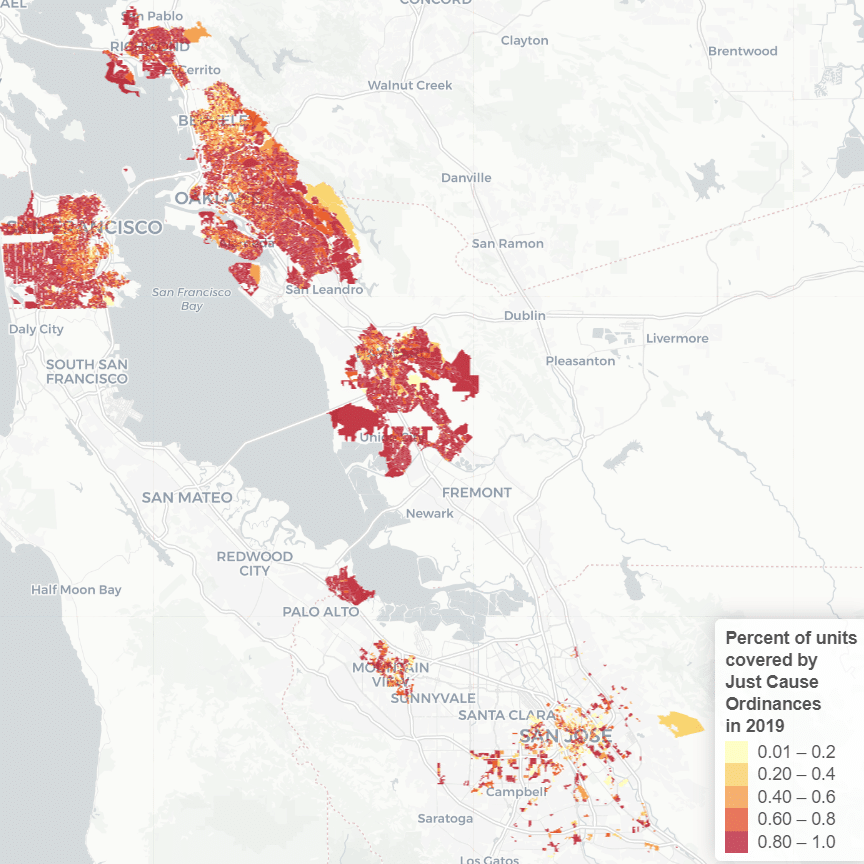

In East Palo Alto, numerous renter protections are on the books, including just cause evictions protections, rent control, condominium conversion limitations, and inclusionary zoning. The case study area (a close approximation of the city) grew by 22% between 1990 and 2013, reaching nearly 17,500 residents. However, even with this growth the area remains a predominantly low-income, minority community.

The strong renter protections in East Palo Alto have surely contributed to helping it avoid gentrification: even with median rent doubling from 1990 to 2013 (from $882 to $1,654, in 2013 dollars), the housing costs here are still some of the most affordable in San Mateo County. Multiple stakeholders have told us of the importance (over and above other policies) of just cause evictions protections. While landlords in other parts of the Bay area may issue notices of eviction even to tenants who have paid their rent on time and followed the rules, such evictions are forbidden in East Palo Alto, a key first line of defense against displacement.

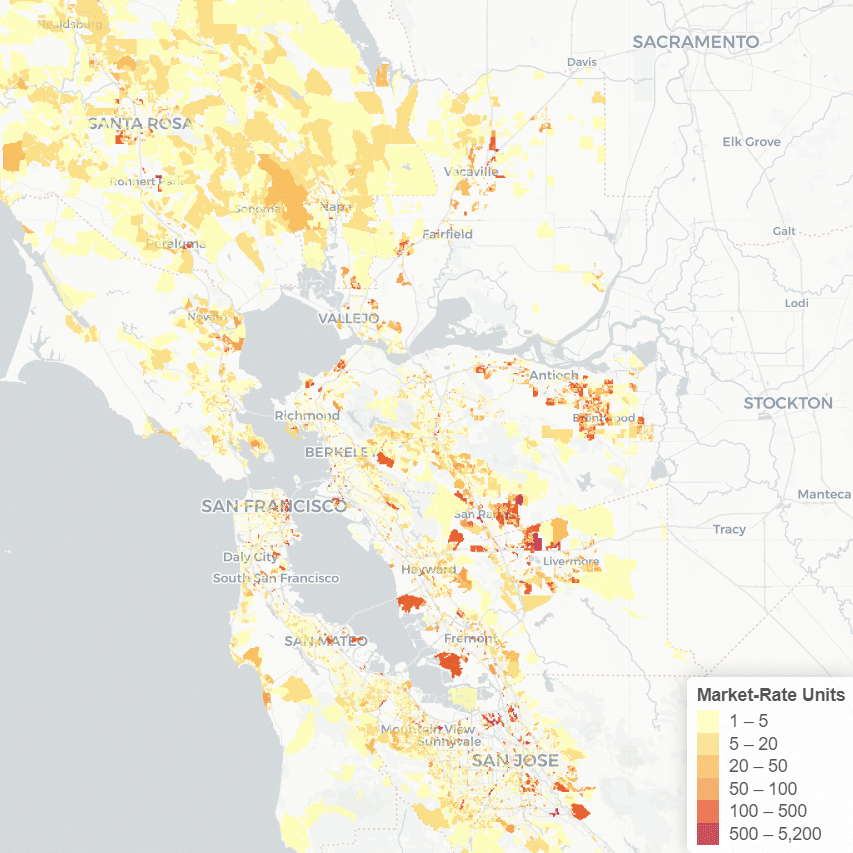

If Chinatown and East Palo Alto are stories of affordable housing preservation, San Jose’s Diridon Station is one of production. Between 1990 and 2013, the case study area experienced growth in its low-income population of 411 households (from 681 to 1,092 households). Aiding in this expansion was the construction of 322 subsidized apartments between 1990 and 2000, including the Parkview Family Apartments (pictured above).

As these case studies show, anti-displacement policies can be instrumental in helping neighborhoods avoid gentrification.

Market Conditions Play A Role

East Palo Alto’s enduring presence as a place welcoming to low-income families may have as much or more to do with lingering perceptions of the area as unsafe and lacking quality schools than it does with the many anti-displacement policies on the books. Simply put, the area seems to still be not quite appealing enough to higher-income, higher-educated people for them to move in. This has kept gentrification away from the area so far.

Similarly, in Chinatown, the constraints surrounding redevelopment have made the area somewhat less desirable to residential real estate speculators. Even if a developer were able to circumvent these strict limitations, to convert a building to a condominium, for example, would likely require major rehabilitation and potentially demolition. Because of this, a conversion project would be a much more difficult and costly undertaking in Chinatown compared to other San Francisco neighborhoods that have been systematically impacted by such types of redevelopment. In some senses, then, Chinatown has avoided gentrification because other areas were—and continue to be—more susceptible to gentrification, or lucrative for speculators seeking to flip residential properties.

While in East Palo Alto and Chinatown, market conditions have made them less attractive to people and capital, in San Jose’s Diridon Station area, it appears the reverse is true: the rapid development of new, market-rate housing in the case study area has been a key to limiting the displacement of residents. The area appears to have added enough new housing to accommodate newcomers, without displacing existing residents. Will these new higher-income residents attract so much high-end retail that the “gritty,” “funky” stores are completely displaced? Will those new retail outlets, and changing perceptions of the area, in turn attract more higher-income residents and investment, displacing the low-income residents who have remained so far? One local expert thinks the neighborhood is reaching its “tipping point,” when displacement will really begin. If the city can protect the existing residents, and build more affordable housing concurrent with the market-rate construction, perhaps it can continue to be a success story going forward.

Through a mixture of policy and market conditions, these three neighborhoods have, so far, avoided the gentrification we expected of them. Together, they show the importance of taking a multi-faceted approach to addressing displacement. Policies must be crafted to meet the specific needs and conditions in neighborhoods and cities.