After the California Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) used our data to advocate for the construction of market-rate housing as an anti-displacement tool back in February, questions have poured into our office: Is it true that market rate development reduces displacement? Does subsidized housing really have no effect? What is filtering?

After carefully reanalyzing our data, correcting for some modeling errors, and adding information on subsidized housing, what we find largely confirms things we already know from Housing Econ 101 – demand and supply matter, but housing is not like most goods and location matters.

So, let’s answers your questions:

1) Can market rate housing ease up the housing affordability and displacement crisis.

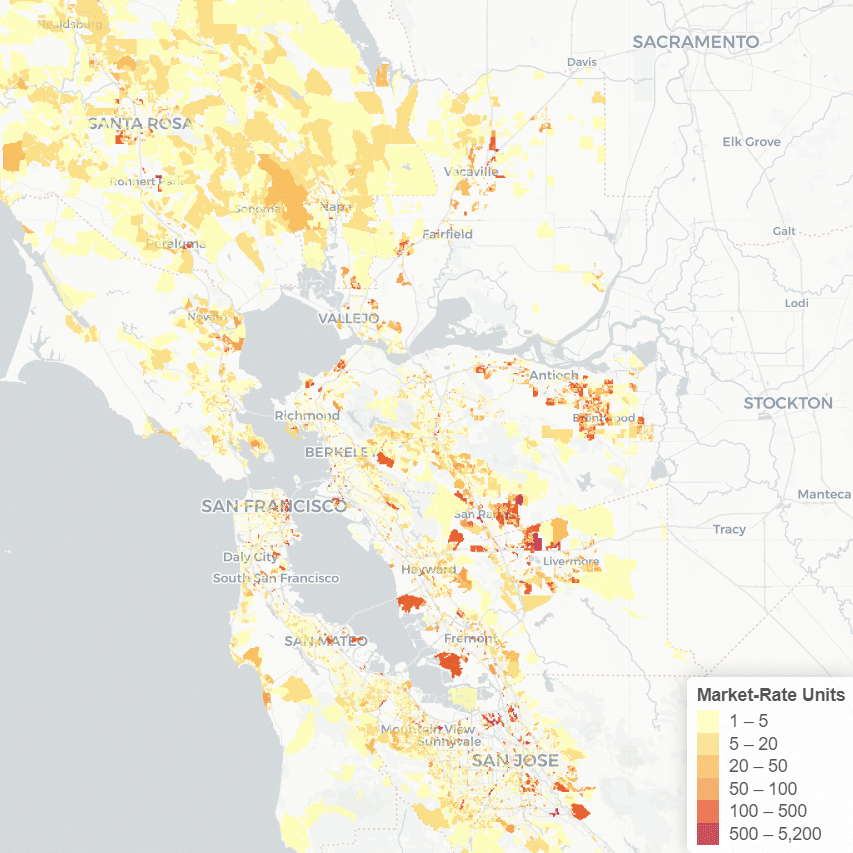

Maybe, but not as quickly as we’d like. Filtering, or the phenomenon in which older market-rate housing becomes more affordable as new units are added to the market, can take generations. Our research shows that while market-rate housing produced in the 1990s can lower median rents in 2013, it was also related to higher levels of housing cost burden for low income households. In terms of our displacement measures, production seems to be related to a reduction in displacement, but the effect from production in the 1990s disappears when you add production in the 2000s. How could this be? Well, it’s possible that the benefits wear off over time and the filtering process is not effective. Or it could mean that other factors are driving the results that are not included in our model and really market-rate housing is not relieving displacement pressures in and of itself.

2) What about subsidized housing?

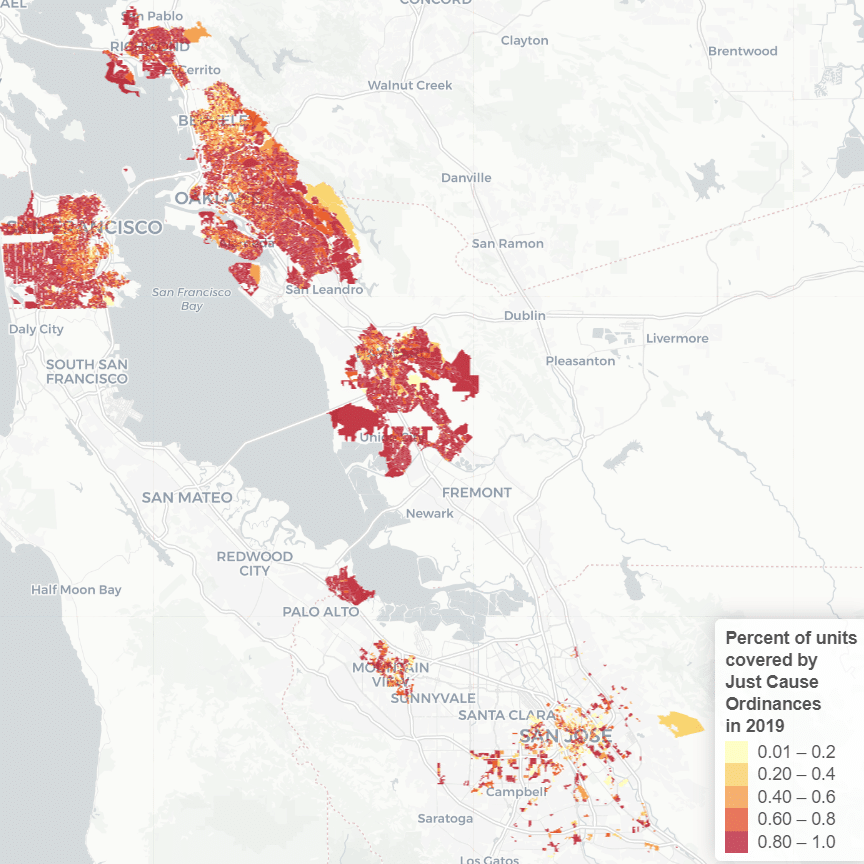

We know that housing is expensive to build, especially here in California. Subsidized housing is no different. The high costs and limited funding streams for permanently affordable housing (especially after the elimination of Redevelopment) were some of the reasons that the LAO report declared the construction of market-rate housing to be the most important strategy. But the LAO report did not actually analyze the impact of subsidized housing on displacement pressures. We do. And we find that subsidized units, that is units produced with Low Income Housing Tax Credits or other state and federal funding programs, have over twice the impact as market rate units in reducing displacement pressures. We’ve been asked if only those lucky few who get to live in the subsidized buildings are protected, or do subsidized units have some sort of protective effect over the whole neighborhood. Unfortunately, our analysis wasn’t designed to answer those questions, as we aren’t able to track who lives in what kind of units and who is being displaced.

3) What about San Francisco?

We know about the extreme shortage and tremendous demands on housing that continue to grow the city’s economic boom. Unfortunately, this mismatch is so great that housing development in the short term simply cannot create a dent in the affordability or displacement crises. When we look at the block group level for San Francisco, we find that neither market rate nor subsidized housing development decrease displacement. Subsidized development does appear to be associated with both a decline in median rents and in housing cost burden for low- income households. But this relationship is complex and may be due to self-selection: subsidized units may be being built in low-cost areas and where low-income residents are less burdened.

4) Why is it so complicated?

As explained by Rick Jacobus in his piece “Why We Must Build” for Shelterforce, market mechanisms work differently at different geographic scales. At the regional scale, the interaction of supply and demand determine prices; producing more market-rate housing will decrease housing prices in the long term and could reduce displacement pressures. At the local, neighborhood scale, however, new luxury buildings could change the perception of a neighborhood and send signals to the market that such neighborhoods are desirable and safer for wealthier residents, resulting in new demand. The differences in our regional modeling versus local modeling would support these arguments.

5) What’s next?

We understand the desire to predict how a development, investment or neighborhood improvement of any kind will change the cost of living in a neighborhood and as well as who lives there. We even wrote a whole literature review of the academic research on the subject. But the research is not fine grained enough to make predictions of how any one project will impact a neighborhood. If there’s any place in the world with the brainpower and data chops to figure this out, however, it’s San Francisco.

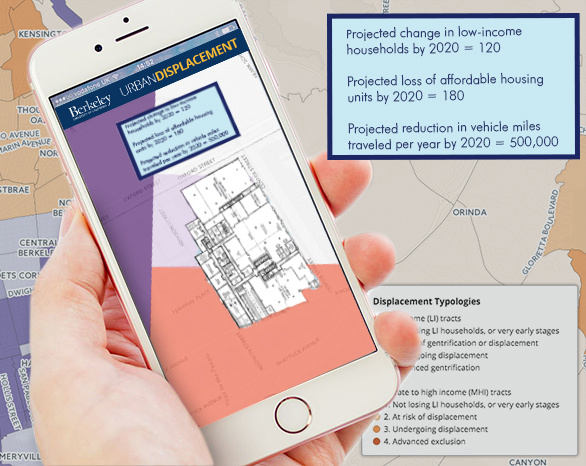

We’re already envisioning the Urban Displacement Project 2.0 to better assess development impact and incorporate new sources of data to improve our predictive ability.