It’s pretty clear that the Bay Area doesn’t have enough housing, but the dialogue around supply-side solutions to the affordable housing crisis tends to be divided. How can we bridge this divide with effective coalition-building to overcome barriers and create housing for all segments of the market? On Tuesday, January 10th, local stakeholders came together at the Silicon Valley Community Foundation to discuss questions around how to create new affordable housing in the second of our four-part workshop series on Investing without Displacement. The series is co-hosted by the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank, the Great Communities Collaborative at the San Francisco Foundation, and the Urban Displacement Project.

“It makes for a more interesting story in the media to turn it into a polarizing discussion, but I think most of us on this panel would agree that it isn’t an either/or endeavor and that we need to build both more market-rate housing and more affordable housing. There is a more nuanced conversation to be had and that we can make happen.” – Kristy Wang, SPUR

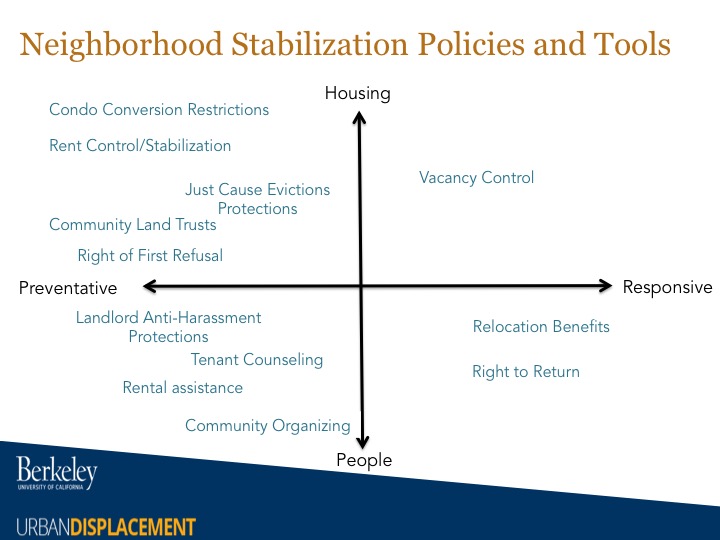

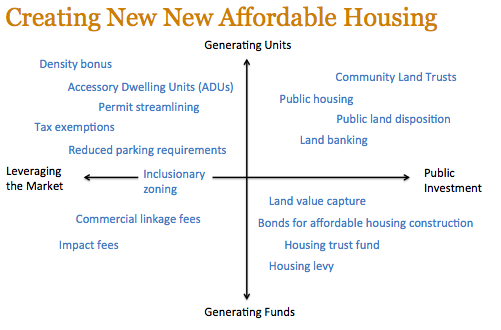

The workshop began with a presentation from Miriam Zuk of the Urban Displacement Project on prosperity and inequality in the Bay Area, lagging production of affordable housing, the jobs-housing mismatch and displacement. The presentation also included a discussion of the limitations of relying on filtering as a supply-side strategy, as well as potential policies and tools to increase the supply of affordable housing (see matrix).

After Miriam set the stage, Naomi Cytron of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco moderated a panel with Gloria Bruce of East Bay Housing Organizations (EBHO), Rick Jacobus of Street Level Advisors, Lewis Knight of Facebook, and Kristy Wang of SPUR. The panel discussion focused on addressing barriers to building housing at all income levels, the importance of inclusive community planning, and coalition-building between the private sector, non-profit housing developers, advocacy groups, and government.

“There’s a segment of the population that needs subsidy if we don’t want them to live in shanty towns or tent cities. And there really is no other way to think about it.” – Rick Jacobus, Street Level Advisors

Here are a few key themes from the panel:

We cannot simply “build, baby, build.”

While there is a definite need to build more housing overall, there is also an imperative to be strategic and build for all segments of the market, not just the top. Rick Jacobus expressed the sentiment that the Bay Area’s prosperity needs to be seen as an asset for affordable housing, but that it is how the resources are distributed that will make the difference:

“I think it’s worth taking a second to step back and take a look at the source of the problem… the source of this problem, at least here, is how much money there is. There is too much money in the Bay Area… lots of people with very high-paying jobs, lots of money from all over the world flowing into companies here, lots of employment here. And that’s a great problem to have and the rest of it is just about how we utilize that money, where does it go, and how do we distribute the benefits of that opportunity. So we can afford to solve this problem, and come up with the money to make housing affordable for people… There are mechanisms that allow us to tap into the economic engine of our economy to help spread the benefit. But it doesn’t just happen on its own. We have to be proactive.” – Rick Jacobus, Street Level Advisors

On the other hand, it’s important to understand why building in hot, gentrifying neighborhoods can potentially cause harm for at-risk communities. Some of the panelists pointed out how resistance to new construction (the infamous NIMBYism) doesn’t just come from the usual suspects today. Gloria Bruce from EBHO discussed the contrast between the NIMBYs of old compared to the dynamic in gentrifying cities today:

“We used to (and still do) spend a lot of time responding to NIMBY folks out in the suburbs…and the NIMBY conversation has gotten really strange and different in the last few years because it has come back into the core cities, like Oakland, Berkeley, and Richmond, and there are people who are saying “not in my backyard” who are people who have actually had their neighborhoods suffer from disinvestment for decades, and those neighborhoods are now starting to look really attractive again. And those people, quite rightly, are saying, ‘this can’t happen without some community investment, without some community engagement.’

[While] some advocates have been scapegoated for the affordable housing crisis, with people saying to them ‘look you’ve become NIMBYs,’ really this is a decades long problem of exclusion, and under-building across the region, which now has become so acute, that folks in the core cities have had to in a weird way take up some of the same tools that more affluent communities have been using for years, and it creates a really confusing and confounding problem for decision-makers to respond to that, and I think we have to keep unpacking that.” – Gloria Bruce, EBHO

Community planning that is both participatory and efficient is key.

Panelists discussed the importance of community input, and the role that community planning can play in speeding up the permitting and entitlement process, if done right. Challenges include the lengthiness of community planning processes, and the fact that those engaged in plans are not always the same people engaged in implementation.

Panelists asked how we can resolve the tension between community engagement and streamlining development. How can we do community planning upfront instead of building by building, in a way that is both inclusive and is efficient so that the housing we need gets built?

“If you’re working upfront about all the infrastructure needs you have, the parts that you want to see, the affordable housing you want to come, upfront so that you can come to terms with what it is the community needs, then afterwards you can streamline a path for development to come and it is faster.” – Kristy Wang, SPUR

So who are the key players that must play a role in increasing the supply of affordable housing?

Local Governments

While local governments may shy away from residential development due to fear that it is a fiscal loser compared to other land use options, panelists point out that this fear relies in part on unconfirmed assumptions, and that residential housing in most cases can be fiscally neutral, if not positive in some cases. Kristy Wang discussed this point:

“Because of Prop 13, there is a limitation to the tools cities have to make sure they’re robust and fiscally healthy…. [However,] foregoing good choices around placemaking and making places where people want to live or people want to go to jobs will backfire in the long run if you are holding out for some jobs that may or may not actually come… Are there other ways cities can get to their [job attraction] goals without artificially limiting their housing?”

Additionally, in spite of barriers such as high land and labor costs, cities can use assets such as vacant public land to increase the supply of affordable housing. Gloria Bruce emphasized the important role of utilizing public land for the public good of affordable housing, especially in this scarce and expensive market. She noted that one way to lower costs and increase production is by ensuring that jurisdictions comply with state law AB 2135, which makes publicly-held land that is no longer needed for agency use available for affordable housing.

Furthermore, panelists made the case for local governments to come together at the regional level, stressing that, in Kristy Wang’s words, “looking at the jobs and housing balance on a city-by-city level is a very narrow-minded way of looking at what our communities need and what’s actually happening on the ground.”

And within cities, elected officials must take leadership in pushing back on reactionary NIMBYism that fails to see the bigger picture. A city councilman from San Mateo joined in the conversation to say that public education must be a part of confronting this thinking:

“It has to be a massive educational effort. Our city is known for doing outreach to the public… It worked for a little while, we were able to get a few things done once we’d done it, but it’s been a few years, and it’s kind of worn off… The trick is to get people involved. We did it before by getting different downtown restaurants to provide food for free, and saying ‘come on in, sit down, have something to eat, and listen.’”

Private Sector and Non-Profit Housing Developers and Advocacy Groups

Given that the mismatch of rapid job growth and slow housing construction is at the root of much of the affordable housing crisis, many have asked where the employers are on this issue, especially since they are ultimately impacted if their employees are unable to find housing in the commute shed. Panelists suggested that if large employers begin to take on the housing crisis, this may open up more space for coalition-building.

Facebook was present, and talked about some of its motivations for joining the conversation – the income inequality right outside its campus’s door, as well as the fact that housing impacts the workers at that campus. Lewis Knight of Facebook called for more openness from private sector actors: “When you’re dealing with intellectual property, you have to have that culture of secrecy… Facebook is a slightly different animal, being a social networking company, being a platform for media. Our ability to have the conversation is our strongest tool. And our ability to be the convener of partnerships to talk about what the issues are is our strongest tool.”

Panelists discussed the need for coalition-building more broadly, including between private sector developers, and non-profit housing developers and affordable housing advocates. Gloria Bruce discussed the fact that these two sets of actors are dealing with many of the same constraints to building new housing – high labor and land costs and a lengthy and uncertain entitlement process. Is there a way for these stakeholders to find common ground?

Moving Forward

We closed with some discussion of what it will take to have a different kind of dialogue around creating new affordable housing, and move to action around more production. Panelists agreed that the different stakeholders – private, public, third sector – need to come together, and that a higher level of regional conversation is needed.

Rick Jacobus called for investment in affordable housing during recessions, a leveraging of the boom/bust cycle. Kristy Wang highlighted the need to build for moderate income families, even if there may be a smaller market incentive to build for this segment: “we need to have the middle to have healthy communities.” Lewis Knight called for closing the transportation gap and building for more mixed-income, multi-family units. Finally, Gloria Bruce reminded us of the “cultural mindshift” of seeing housing as a human right:

“For me, the long-term game-changer is the cultural mind shift that cities and people stop evaluating housing based on its fiscal impacts or economic worth and just say it’s a human right. How are we going to figure out how to give it to everyone, to not judge people who don’t have it, to make sure it’s decent and okay for everyone?”

The next workshop in the series will discuss preserving existing affordable housing stock. Stay tuned…