When we talk about addressing the housing shortage and stemming the tide of displacement, preservation strategies have sometimes been absent, as conversations on affordable housing often default to construction of new units. However, preservation of existing affordable housing, both subsidized and naturally-occurring, is an essential piece of the puzzle.

Preservation can be more cost-effective. While it is true that new affordable housing needs to get built, and we need to find ways to build better coalitions toward this end, there are also large barriers to building: NIMBYism, permitting, land costs, labor costs, and fiscalization of land use, to name a few. According to HUD, preservation of affordable housing is estimated to cost between one half and one third less than new construction. And we can’t rely on filtering of new market rate units; with filtering come housing quality issues that need to be addressed from a habitability perspective.

On Wednesday, March 1st, local stakeholders came together at the Rockridge Library in Oakland to discuss how to best preserve and augment existing affordable housing stock, in the third workshop of our series on Investing without Displacement.

“Affordable housing developers are very good at new construction, but to purchase a home where you don’t know the conditions of it and you don’t know who lives there, let alone their income, it’s a bit of a Pandora’s box. So a lot of the world of preservation right is now is to try to create the infrastructure we need to take on this work – what are the financing tools? What kind of capacity do organizing groups and developers need, and what are the programs that we need?” – Geeta Rao, Enterprise Community Partners

To frame the conversation, Miriam Zuk (Urban Displacement Project) kicked off the workshop with a presentation detailing the rapid loss of affordable housing in the Bay Area, quality issues that can sometimes come with naturally affordable housing stock, and the importance of leveraging code enforcement.

Next, Geeta Rao of Enterprise Community Partners moderated a panel with Kate Hartley from the San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, Rosemary Bosque from the City of San Francisco’s Code Enforcement Division, and Felix AuYeung from MidPen Housing. The panelists discussed the complexity of preservation, and the capacity that needs to continue to be developed to make preservation possible at scale.

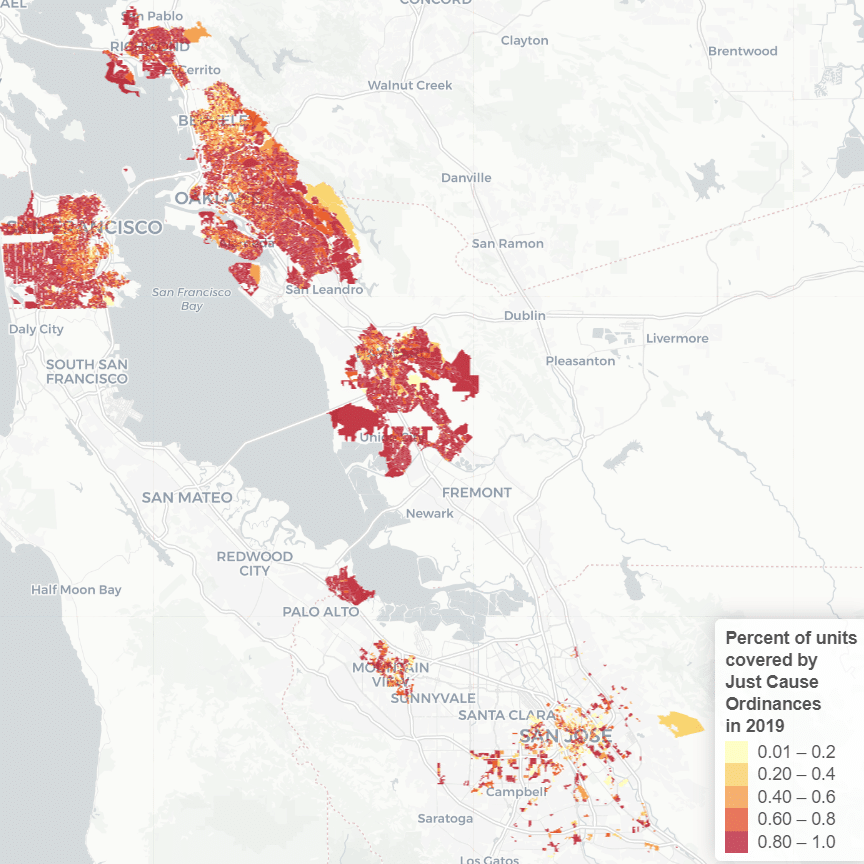

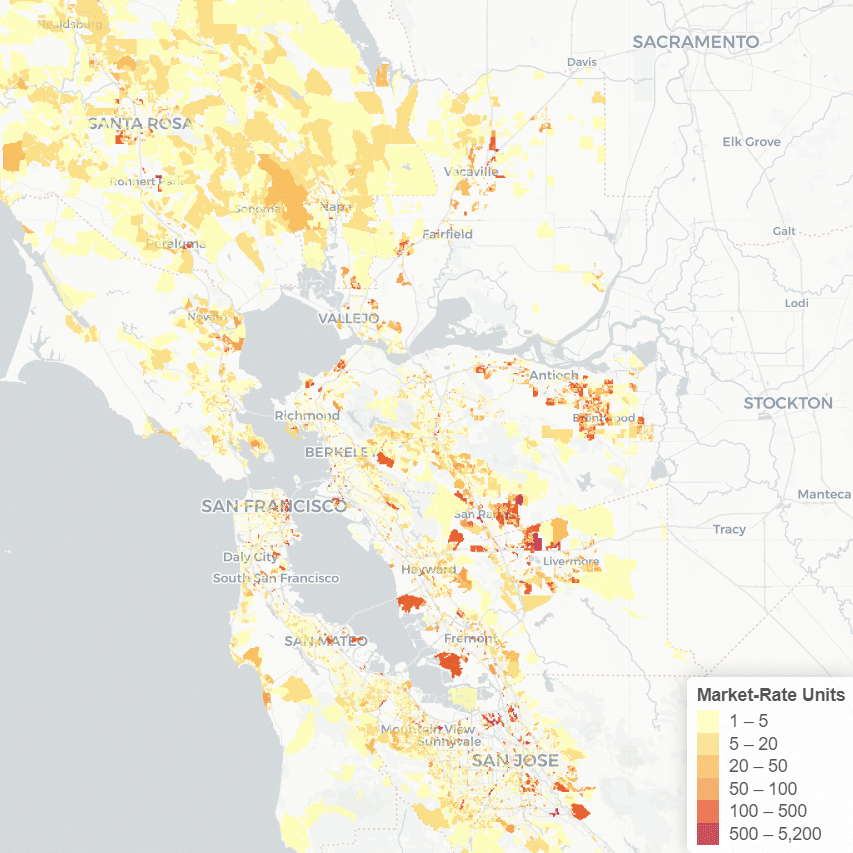

Rapid loss of affordable housing in the speculative market

Naturally occurring affordable housing, or housing that is affordable without public subsidy, may be affordable due to age, quality, or even rent control, and is at risk of becoming unaffordable due to speculative market pressures.

In terms of rent-controlled units, Kate Hartley (San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development) highlighted the challenges of state-mandated vacancy decontrol, which means that when a tenant vacates a unit, rent can be raised to market rate. Hartley noted that while San Francisco has 175,000 units of rent-controlled housing stock, when those units turn over, they become unaffordable again. In a hot market like San Francisco’s that means, in Hartley’s words, “we do lose those units’ [affordability] every single day.”

Naturally occurring affordable housing is also at risk of being purchased and flipped to make a profit in the speculative market. Thus, panelists noted the value added to preservation when it proactively moves naturally occurring affordable housing units off the speculative market.

“These households are so happy. Even if they get a rent increase, they’re like ‘man, I won the jackpot because I’m not gonna get evicted since my building is now off the speculative market.’” – Kate Hartley

Specifically, Hartley detailed the San Francisco program, Small Sites SF, that has allocated $75 million since 2014 to non-profit acquisition and rehabilitation of multi-family apartment buildings, which is stabilizing housing for people at significant risk of displacement: 30% of the people whose units were acquired and stabilized were under active evictions proceedings (which were stopped through this program), 30% make less than 50% area median income (AMI), 15% are children, and 10% are disabled. Hartley emphasized the stakes of preserving affordable housing for these and other low-income people who are being forcibly pushed out: “If those evictions had gone through, no way those people could have stayed in San Francisco, or arguably the larger Bay Area. People are at risk of homelessness. This is how homelessness happens.”

Code enforcement can be leveraged in innovative ways toward preservation

Another means of losing naturally occurring affordable housing is when the housing deteriorates to a point of inhabitability, and is rehabilitated for market-rate occupancy. Code enforcement can even trigger this process when buildings get condemned and eviction notices get delivered to current tenants. This was the story of the San Francisco Department of Building Inspections for some time, which Rosemary Bosque describes as having had “a bunker mentality” in the 90s. During that period, the Department’s main operations were to issue 30, 60, and 90-day notices of evictions.

However, code enforcement can also be leveraged in innovative ways toward preservation. The Department has since shifted, and today emphasizes community partnerships, and the role of code enforcement in stemming the tide of displacement. In 1995, the Department started a code enforcement outreach program, bringing in community-based organizations like Causa Justa Just Cause and the Chinatown Community Development Corporation, as well as groups that represent residential hotels. Bosque emphasized the importance of “making sure that the code enforcement position in the city job description requires community based experience.”

Examples of innovative code enforcement employed by the SF Department of Building Inspections include:

- Listing violations online for transparency purposes

- Working with community outreach and the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development to ensure relocation fees in the event that a tenant does ultimately need to be displaced due to substandard housing conditions

- Requiring that property owners make an attempt to legalize substandard illegal units rather than evicting residents and flipping properties

- Using code to preserve residential hotels

- In response to an epidemic of fires in single residence occupancies (SROs), the agency engaged in partnerships to to create legislation requiring that landlords put together an action plan and damage report, instead of letting buildings sit unattended.

Scaling up preservation is difficult, but possible

Preservation is complex; Hartley noted the desire to scale up the Small Sites program described above, but was also forthright about the challenges: “Think about the complexity of building after building, all of these tenants with their own stories and their own ability to pay rent.”

Felix AuYeung from MidPen Housing also discussed the challenge of time-intensive processing for acquisition-rehabilitation efforts, suggesting that economies of scale are key to making preservation work. “Project-level scale is really important. We’re looking at a proposal for 160 units, and I’m spending less time on that than I am on the acquisition of nine units. How do we weigh that as a nonprofit for impact?” He pointed out that the same arduous loan processing, auditing, and reporting requirements are necessary at both ends of the spectrum scale. Thus, “there’s some scale that’s really important for us to make things work, to make the lines not cross in terms of revenue versus expenses.”

However, panelists are optimistic that scale is attainable, and with the right resources and political will, preservation can flourish as an anti-displacement strategy.

In order to achieve scale, some key pieces need to fall into place. First of all, preservation needs increased funding. While bond measures like Oakland’s Measure KK are promising, funding for preservation overall is extremely limited – despite the fact that it may be more cost-effective than construction of new affordable housing. Increased funding for preservation projects would create the potential to provide large-scale protections for renters currently in the speculative market.

Partnerships are critical. While AuYeung discussed challenges of smaller sites, he asserted that what can make preservation work for smaller sites are effective partnerships: “CDCs [community development corporations] that are operating in a smaller neighborhood could get to scale by having smaller properties, having one property manager, potentially even combining their financing so that they consolidate loans and audits – that would require a nonprofit that has some scale within a particular neighborhood.”

Hartley and Bosque both also emphasized that they would not be able to succeed in their preservation efforts without their partnerships with local non-profits. Panelists emphasized that coalition-building needs to extend to a regional scale to solve this regional problem.

Moving Forward

Finally, panelists shared closing thoughts on how to leverage the capacity of preservation efforts to augment existing affordable housing stock:

Rosemary Bosque (City of San Francisco’s Code Enforcement Division) encouraged the audience to “always look at the code enforcement in your city. There may be ways to strengthen it. All the jurisdictions within California are facing older housing stock. We need to make sure that’s taken care of at the state level.”

Felix AuYeung (MidPen Housing) reinforced the need to get a funding infrastructure in place for preservation: “If we can get these pots of money in place, and have the structure ready to pounce for when prices calm down, there’s some long-term planning to be done.”

Kate Hartley (San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development) stressed that larger buildings may represent larger opportunities: “It’s important to get out of the 4, 5, 6 unit focus. What will make a difference is if we can start lending on the 20, 30, 40, 50 units, stabilize them, get them out of vacancy decontrol, and move them into permanent affordability.”

Check out more insights from all three Investment Without Displacement workshops – neighborhood stabilization, production of new affordable housing, and this preservation workshop at https://www.urbandisplacement.org/IWD2017.