Displacement: The Misunderstood Crisis

When we think of gentrification and displacement, we typically envision a hipster – young, professional, and probably white — in the Mission District or Brooklyn at the peak of the real estate

Displacement, which is distinct from gentrification, occurs in many different forms, places, and moments. While gentrification refers to a process of neighborhood change that encompasses local increases in real estate investment, household income, and educational attainment, displacement occurs when housing or neighborhood conditions force moves. Displacement can be physical (as building conditions deteriorate) or economic (as costs rise). It might push households out, or it might prohibit them from moving in, called exclusionary displacement. It can result from reinvestment in the neighborhood — planned or actual, private or public — or disinvestment.

Thus, displacement is often taking place with gentrification nowhere in plain sight. In fact, stable neighborhoods at both the upper and lower ends of the income spectrum are experiencing displacement.

On the upper end, our Urban Displacement Project shows that in total, the Bay Area’s affluent neighborhoods have lost almost twice as many low-income households as have more inexpensive neighborhoods. For instance, in Berkeley, since 2000, affluent neighborhoods have lost 672 low-income households – almost one in five – while its few remaining low-income neighborhoods lost 278 (4%), and its gentrified neighborhoods actually gained 135 low-income households. Across the Bay, Mountain View also lost one in five low-income households from its affluent neighborhoods, while experiencing almost no displacement in its low-income and gentrified neighborhoods.

On the lower end, neighborhoods such as Pittsburg, located in the outer areas of the region and experiencing minimal gentrification and investment, are also losing low-income homeowners, often to foreclosure. Other neighborhoods, like the vicinity of Diridon Station in San Jose, lost their low-income households decades ago in the 1980s, via redevelopment projects that have been slow to materialize. Still others, like the Monument Corridor in Concord, are experiencing the eviction of tenants now in anticipation of future demands related to the tech economy. At the same time, traditional working-class communities like Redwood City are deliberately remaking themselves to cater to new demand.

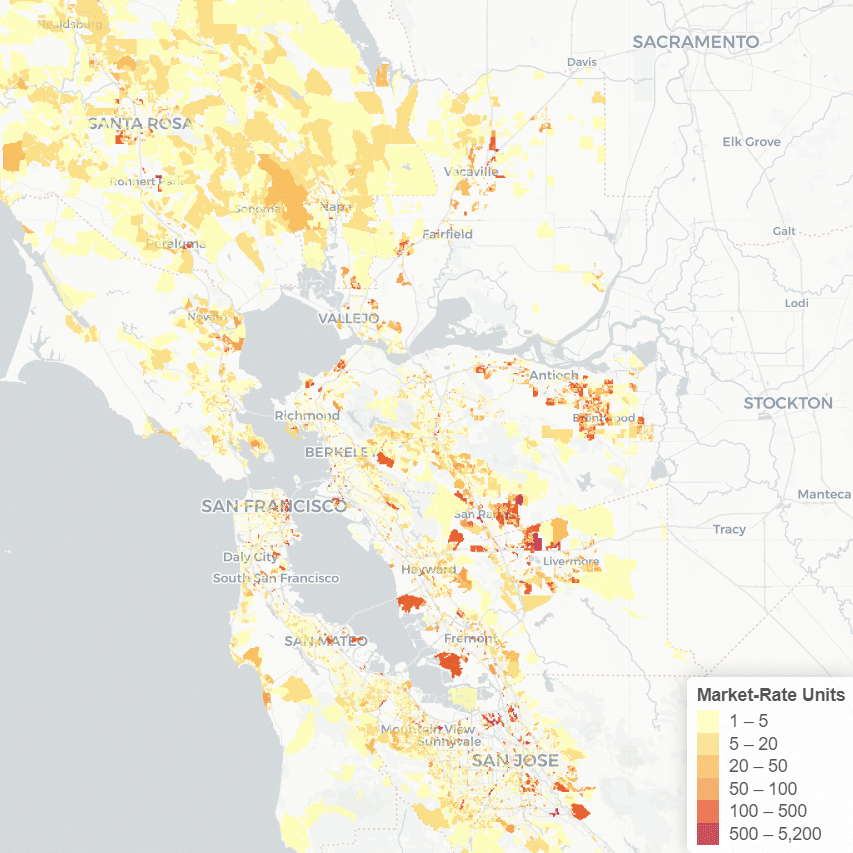

When households leave, where do they go? Whether pushed out of more or less affluent areas, low-income households most likely end up in different low-income neighborhoods. More than twice as many low-income households moved into inexpensive areas as into more affluent. The region’s two biggest cities, San Francisco and San Jose, have accommodated almost half of the in-movers, mostly in their lower-income neighborhoods. And when low-income households move into more affluent areas, it is typically to places like Brentwood or Fremont.

These patterns are of concern because low-income neighborhoods tend to lack the quality of amenities and opportunities available in middle- and higher-income areas. Constricted mobility patterns like this show the value of HUD’s redoubled effort to affirmatively further fair housing. Living in a more affluent – or revitalizing — neighborhood gives low-income families better access to education and a higher quality of life.

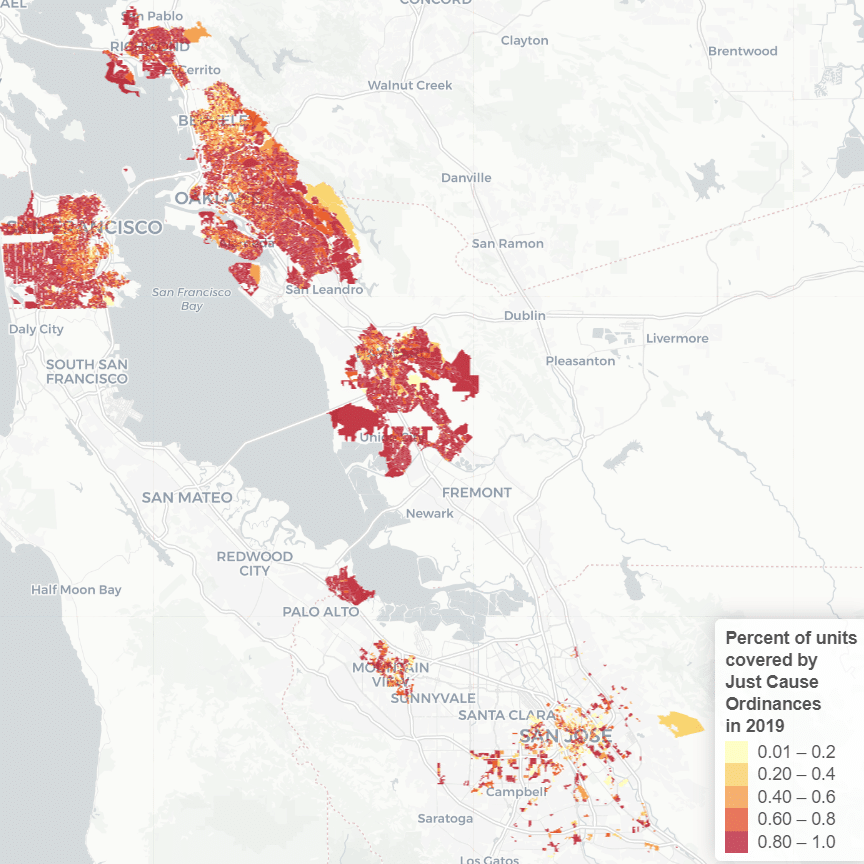

But even more effective than opening up new areas to fair housing is preventing the low-income households already there from being forced to leave. Anti-displacement policies stabilize communities and ensure access to opportunity. The challenge we face is how little is known about what works best to keep families in place. Cities have been slow to adopt new policies. In coming months, we will discuss our results in more detail, including offering case studies of policies that have been effective.

Photo credit: KQED.org.