The year is 2030. Protesters gather around yet another apartment building where long-term residents are being evicted to accommodate newcomers.

We must be in San Francisco. No, we’re in Oakland.

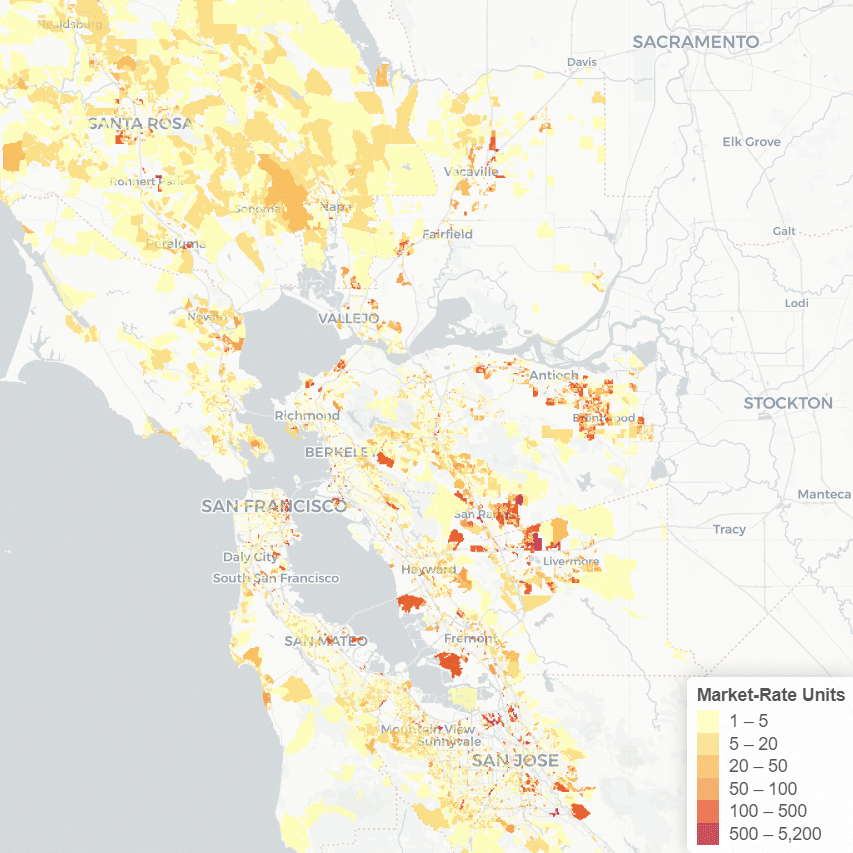

Guess again. It’s Hayward. Or, Concord. Or perhaps, Santa Rosa. In 2030, these and many other Bay Area communities may realize that their neighborhood has turned the corner from displacement risk to reality.

We should have seen it coming. Just like the region’s core, these suburbs feature characteristics of the hottest rental markets. There are job centers nearby, the housing and neighborhoods have historic character, and there is access to fixed-rail transit – or firm plans to build train lines. These are some of the factors that create risks of future displacement.

Cities throughout the region are aware of the housing crisis. But they often think that they are somehow different, protected from the pressure on housing prices. So, for instance, they build new train extensions, but don’t expect new housing demand. Then, their housing markets are not ready for the newcomers, and their policies do not protect the existing community.

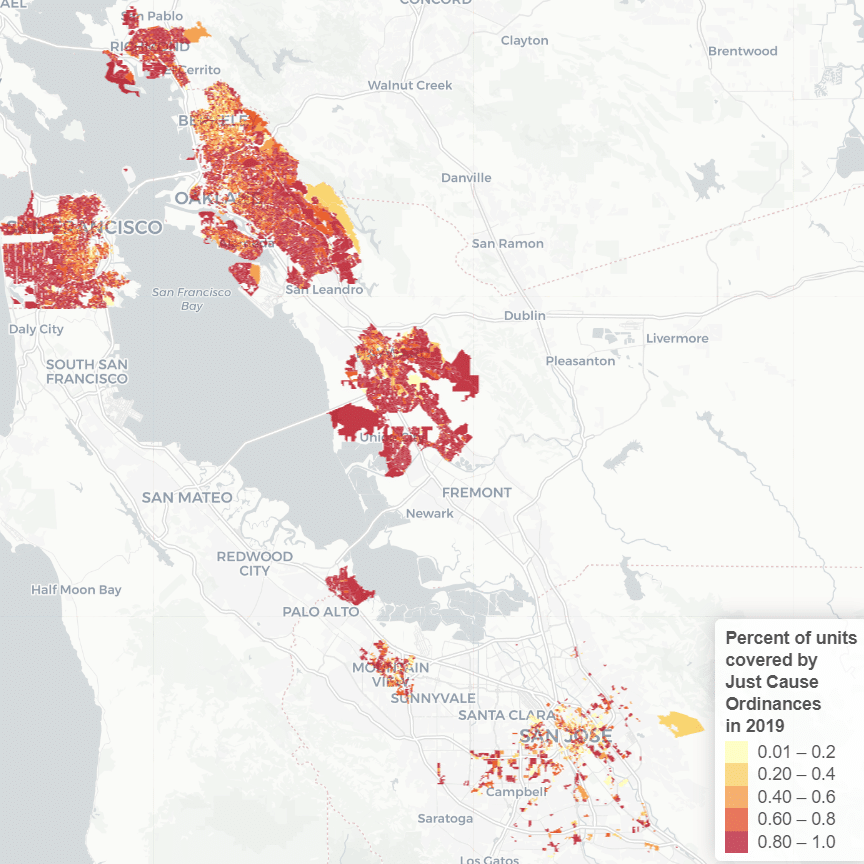

We need to understand the dynamics of neighborhood change better in order to help cities prepare. For Bay Area residents, our Urban Displacement Project tells the story of change – recent and projected — in each neighborhood in the region. This research indicates that the region’s current housing crisis is not even half over. Families, community groups, and cities can use our new mapping tool to see where their neighborhoods fit into the spectrum.

As residents witness the change in neighboring communities, many are wary about what is in store. But gentrification and displacement have not, and are not predicted to, spread across the entire region indiscriminately. In fact, more than half of neighborhoods in the nine-county Bay Area are quite stable, or just becoming poorer. Despite anxiety over the potential for an influx of high-income households, places like East Palo Alto or Marin City have other housing market challenges they might better focus on, such as the need to build more new affordable housing or improve the conditions of the existing housing stock.

Our research funders, the California Air Resources Board and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, were particularly interested in understanding how public investment, from infrastructure investment like bike lanes and landscaping, to fixed rail transit systems, might hasten displacement. Looking specifically at the role of fixed rail transit, our study found that not just the investment itself, but also planning for the transit investment, can accelerate processes of displacement.

Yet the existence of transit investment also creates the possibility of mitigating displacement: as improvements are planned and developers’ interest is piqued, cities can generate more funding for subsidized housing through impact fees and other measures, and change local zoning to protect existing affordability. Working together, regional agencies such as the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments can use funding as a carrot to incentivize cities to prevent the displacement of existing residents.

Even though many Bay Area neighborhoods are at risk of displacement or exclusion, such change is not inevitable. Some places are experiencing much lower levels of displacement than we expected to find. Why? They have policies in place that preserve affordability and protect existing residents. One example is San Francisco’s Chinatown, where a well-organized community has used zoning proactively to preserve the existing character and demographic composition of the neighborhood in the face of investment pressures.

In the coming months, we’ll be sharing more examples of both policies that are preserving residential neighborhoods, and ways to prevent displacement of businesses and jobs. Stay tuned!

This single-room-occupancy apartment building in San Francisco’s Chinatown is one of many that have withstood displacement pressures in the surrounding area through deliberate community organizing and zoning, which have preserved the local stock of low-rent housing.